grassroots progressive christianity a quiet revolution by hal taussig in chicago a tony award–winning piano player improvises a jazz t

Grassroots Progressive Christianity

A Quiet Revolution

By Hal Taussig

In Chicago a Tony Award–winning piano player improvises a jazz tune

while some thirty church members dance and another hundred sing . . .

in Phoenix a congregation can hardly wait for new scholarship on who

Jesus was as a first-century Galilean . . . in Boston the United

Methodist bishop, a woman, appointed a pastor to the new church formed

explicitly to affirm the full participation of gays and lesbians . . .

in semirural Washington some nuns are entering the twelfth year of

their “Earth Ministry” dedicated to a new ecological consciousness . .

. in Decatur, Georgia, a group of women that started worshipping in

the late 1990s in each other’s houses has now settled into life

together as a feminist congregation.

In Manhattan the thirty-year-old woman associate pastor preaches about

urban poverty the morning after she was a stand-up comic in the

church-sponsored night club . . . in Delaware the visiting leader of

the Center for Progressive Christianity helps a group of churches

examine the relationship between science and religion . . . in

Wichita, the second largest United Methodist church in Kansas baptizes

a child of an openly lesbian couple . . . in California’s wine country

hundreds of clergy gather to hear leading biblical scholars from

around the country . . . in a Capitol Hill neighborhood Episcopalians

form a communion circle of more than one hundred people of different

races, sexual orientations, and classes . . . in Philadelphia’s

ultraconservative Roman Catholic diocese hundreds gather in an urban

neighborhood parish church each week to challenge each other’s and the

archdiocese’s racism . . .

In Alabama 700 people gather to hear an Episcopalian author talk about

why Christianity must change or die . . . in Rochester, New York, an

entire parish decides to break with the Roman Catholic hierarchy and

ordain a woman to the priesthood . . . in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, a

local Mennonite church which proclaims itself as a refuge for divorced

people, gays, and lesbians has grown so much in the past fifteen years

that it has gone through two building programs . . . in countless

cities “faith sharing groups” have challenged Roman Catholic

prohibitions by having eucharists in their homes without priests.

New voices celebrating a lively, open-minded, and open-hearted

Christianity are emerging at the grass roots across America.

Comfortable with their own faith, they also insist that they are not

better than Jews or Muslims. In contrast to the old liberals of the

1960s and 1970s, these new voices are just as interested in

spirituality as they are in justice. With much more confidence than

Christians of the mid-twentieth century, this new momentum strongly

affirms both intellectual analysis and emotional expression of one’s

own faith. With constituencies of both inspired youth and seasoned

leaders, new groups advocate strongly for the causes of women, gays

and lesbians, and the environment. Weary of materialist decadence,

these voices proclaim a Christian practice that helps individuals

resist the dominant American paradigms.

A New Spiritual Home: Progressive Christianity Emerges at the Grass

Roots, my most recent book just published by Polebridge Press, is

about these new voices and their new movement. It describes,

celebrates, and assesses them. Less a proposal for some new dream of

Christianity, this book is the product of a yearlong research team

having found some astonishingly new developments with promise for a

very different future. Indeed, what the nationwide research shows is

that a similar and new kind of Christianity has emerged at the grass

roots across America in the last fifteen to twenty years. This

research project has dared go below the surface of reactionary

Christianity struggling to hold on to the past or fading denominations

unsure of what they represent. Underneath this veneer, it turns out,

is a nationwide impulse well underway that is already practicing a new

kind of Christianity.

These new voices do not make up the majority of Christians. But they

are refreshingly confident about a new lease on Christian expression

that is strikingly different from both the fundamentalism and the

flailing denominations often featured in the American press. Rarely

self-aware on regional or national levels, this new momentum is just

discovering itself. Only within the last six or seven years has it

gathered on more than the grassroots level. Because it is both within

and outside ordinary Christian denominations, this phenomenon has no

clear leadership. Like most grassroots experiences, it is bubbling up

in a variety of forms. Like the seeds growing secretly in the gospel

parable, the new voices, once identified, surprise us with their

fullness.

Nor are these new communities— the research has discovered literally

thousands of them —a result of some national program or initiative

from above. Although they exist clearly within all denominations,

including Catholicism, their emergence is not in response to an

overarching collaboration among the various religious bureaucracies.

Nor are they a product of some popular and charismatic national

preacher. Rather, in their similarity, they come from an unorganized

but broad-ranging kind of Christian response to felt needs for vital

spirituality, intellectual integrity, new ways of expressing gender,

an alternative to a Christian sense of superiority, and a desire to

act more justly in relationship to the marginalized. This is a

dispersed grassroots phenomenon across a wide range of

denominationalism.

The Term “Progressive Christianity”

I am calling this emergent movement of Christianity in the United

States “progressive Christianity.” It is not yet the perfect term, and

as the phenomenon develops, a better term may come into view. This

term is descriptive inasmuch as “progressive” is a term being used

increasingly by the people themselves who make up this movement.

Although there is far from unanimity for the term, there are some

clear signs of it working as at least a provisional word this kind of

Christian uses for himself or herself. For instance, the only national

organization to which this book’s subject matter approximately

corresponds is the Center for Progressive Christianity. Theologian

John Cobb has edited a book in the past five years that proposes a new

justice-centered Christianity and calls it “progressive Christianity.”

Author Marcus Borg, whose books have become quite popular with this

new kind of Christian, dedicates his recent The Heart of Christianity:

Rediscovering a Life of Faith to a couple of Texans and their

“commitment to progressive Christianity.”

Other terms might be used, but have distinct disadvantages. To a

certain extent the term “liberal” might apply. Certainly the

commitment to intellectual open-mindedness and to acting for social

justice has been at the center of the self-understanding of Christians

who think of themselves as liberal over the past fifty years. However,

many of “liberal” churches still exist with this focus and without

having developed the new excitement about spirituality and expressive

worship I have discovered across the country in so many other socially

conscious and intellectually stimulating churches. So I do not use the

term “liberal” for the vital new movement I want to describe. Rather,

I consider a “liberal” church to be one that has not changed much in

the past twenty years and has maintained a strong intellectual

openness, an emphasis on social justice, a traditional worship with a

lot of preaching and very little participation or expressiveness by

the people, and not much attention to feminism, gay and lesbian

issues, spiritual renewal and experimentation, or other religions. The

new nationwide trend profiled in A New Spiritual Home emphasizes

creative worship, feminism, gay-friendliness, and new attitudes toward

other religions. In this regard, “progressive” seems preferable to

“liberal” in designating the new movement, while “liberal” is a

convenient term for the churches with an older mix of traditional

piety, intellectual rigor, and emphasis on social justice.

“Open-minded” and “open-hearted” as a combination has much to commend

it in relationship to this new movement. In contrast to the way I am

using “liberal,” it connotes the new spiritual vitality of this new

movement. Unfortunately, this combination is part of the new

denominational motto of the national United Methodist Church: “open

minds, open hearts, open doors.” While pleased that this denomination

wants to claim open-mindedness and open-heartedness for all its

churches, I know as a United Methodist pastor that United Methodism is

much more conventional, much less creative, and much less

adventuresome than the amazing set of Christian churches,

organizations, and individuals documented in my research.

Something also needs to be said about the term “Christian” in the

descriptor “progressive Christianity.” Although the emergent movement

I am describing does not think of Christianity as better than other

religions, that does not mean that the participants in this movement

are not Christians. Some of those described in this book are somewhat

uncomfortable with the self-designation “Christian.” And, they do seem

quite different from the majority of Christians in the United States.

Nevertheless, there does not seem to be a better term for people who

talk about Jesus, read the Bible regularly, and practice the rites of

breaking bread and baptizing those new to the community as this new

movement does. So I have concluded that just because these new

Christian communities do not conform to some of the conventional

models does not mean that they are not Christian.

Even though forms of conservative or reactionary Christianity may

dominate the American scene and even embarrass some participants of

the new movement, I am quite sure that it is not only accurate, but

also important to call this new movement “progressive Christianity.”

This distinguishes progressive Christians from evangelical Christians,

cultural Christians, New Age adherents, mainline Christians, Jews,

Muslims, and many Quakers and Unitarians. Just clarifying these

differences helps to identify the rather spectacular new promise this

movement brings into view.

The Five Characteristics

of Progressive Christianity

1. A spiritual vitality and expressiveness. The wide-range of churches

and groups in this movement—in contrast to the traditional liberal

Christians—are not just heady social activists and intellectuals. They

like expressing themselves spiritually in meditation, prayer, artistic

forms, and lively worship. It is astonishing how similar these

spiritual and worship expressions are, even though they come from

widely different denominations and parts of the United States. A New

Spiritual Home details five aspects of this new spiritual vitality:

participatory worship, expressive and arts-infused worship and

programming, a reclaiming of discarded ancient Christian rituals (for

example, baptismal immersion and anointing with oil), a wide variety

of non-Christian rituals and meditation techniques, and development of

small groups for spiritual growth and nurture.

2. An insistence on Christianity with intellectual integrity. This new

kind of Christian expression is devoted to and nourished by a

wide-ranging intellectual curiosity and critique. It interrogates

Christian assumptions and traditions in order to reframe, reject, or

renew them. God language, the relationship between science and

religion, and postmodern consciousness are the major arenas of this

intellectual rigor.

3. A transgression of traditional gender boundaries. These groups are

explicitly and thoroughly committed to feminism and affirmation of

gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. The feminism is

regularly a part of new kinds of family and child-rearing dynamics.

The extent of gay-friendliness is illustrated by at least seven

national Christian movements devoted to support of GLBTs and rooted in

thousands of local churches.

4. The belief that Christianity can be vital without claiming to be

the best or the only true religion. In contrast to mainstream

Christianity’s lukewarm “tolerance” of other religions, progressive

Christianity pro-actively asserts that it is not the best or the only.

Progressive Christians take pains to claim simultaneously their own

Christian faith and their support of the complete validity of other

religions.

5. Strong ecological and social justice commitments. The longstanding

Christian interest in aiding those who suffer or are poor is continued

in progressive Christianity. Similarly, this new movement is committed

to old style liberal social justice programming and peace advocacy. In

addition, however, there is a passion for environmentalism, including

explicit attention to changing life style and consumer patterns in

order to lessen the human footprint on the Earth.

Where to Find Progressive Christianity

One of the most surprising aspects of my team’s research was the

breadth and depth of this new phenomenon of progressive Christianity.

We found it in all geographical sections of the country and in urban,

small town, and suburban America. There are two major forms of this

emerging kind of Christianity. The first is not at all a new form per

se, but is a powerful expression the new progressive Christianity.

The research found over one thousand local churches which fit the five

characteristics described above. Some fifty of them are profiled in

the book, A New Spiritual Home. They include some of the churches

mentioned at the beginning of this article. Another is the Park Slope

United Methodist Church in Brooklyn, New York, a diverse congregation

bursting with drama in its worship, social justice and ecology in its

program, and new congregation-designed windows celebrating liberation

figures of the twentieth century. Like Calvary UMC in West

Philadelphia, Glide Memorial UMC in San Francisco, Judson Baptist

Church in Greenwich Village in New York, and the Church of the Savior

in Washington, D.C., Park Slope UMC has drawn deeply on its diverse

neighborhood.

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Houston, Texas, which marches in the

city’s annual gay pride parade, has a weekly worship service intended

for people who have never developed a church affiliation or who may

have left the church because they no longer felt comfortable or

connected or because “organized religion” no longer seemed relevant to

their lives. This Sunday evening, called “Engaging the Questions,”

bursts the regular Episcopal bonds. The service includes active

discussion of questions such as, “What does it mean to be a person of

integrity?” “What is a person of faith?” and “Is there a purpose to

human life?” “Engaging the Questions” is not, however, a mostly

cerebral engagement. It integrates discussion of big questions into

dramatic performances, eclectic music, and artistic expression of

biblical texts.

The North Raleigh United Church in North Carolina has a strong

relationship to Muslim worshipping communities and gives 51% of all

its income to ministries beyond itself. The Jesus Our Shepherd Parish

in Allentown, Wisconsin, is a Catholic Church with three married

priests. The Circle of Grace Community Church in Decatur, Georgia is a

feminist-based house church. Noe Valley Ministries in San Francisco

sponsors eight different hours of worship or meditation: five “quiet

times” each weekday morning, one meditation service on Sunday morning,

a Wednesday morning “prayer circle,” and the regular Sunday morning

worship. This intense spiritual focus has not impeded NVM in social

justice programming. NVM participates in the larger San Francisco area

efforts of Habitat for Humanity, the Religious Witness for the

Homeless, the San Francisco Food Bank, Foundations for Education,

Inc., La Casa de las Madres, Raphael House, and Sequoia.

Proudly proclaiming itself as “an alternative to church as usual,”

Christ Community Church in Spring Lake, Minnesota, has a strong sense

of spirituality and worship expression, eschewing the old liberal

dichotomy of head and heart by focusing simultaneously on the “awe of

worship” and a ministry of theological inquiry. The CCC mission

statement claims Christian identity full-heartedly but without a sense

of superiority over other religions: “Christ Community finds its

window to God in the face of Jesus while affirming the quest and

insight of other faiths: opening ourselves to dialogue and mutual

enrichment in our pluralistic world.”

The great majority of Extended Grace Faith Community (Lutheran) in

Grand Haven, Michigan, is under thirty-five, and “led by young adults,

many of whom have been hurt or made to feel unwelcome in traditional

church environments.” The main worship and gathering place for these

people is a former Steakhouse bar and restaurant. Although many of the

readings come from Buddhism or Sufism, the worship is “unashamedly

Christ-centered.” Each Sunday worship service contains a communion

meal right alongside eastern meditation practices. Extended Grace is

an official “Reconciling in Christ congregation,” the Lutheran term

for local churches that have made an official Affirmation of Welcome

to GLBT people.

The second main form of progressive Christianity can be called “the

Roman Catholic resistance.” Although official Roman Catholicism in

America has in the past twenty-five years come increasingly under the

control of centralized and reactionary hierarchy, two factors have

come together to form a significant faction of genuine American

Catholicism. These two factors are: 1) the foundational reforms to

Catholicism articulated in the Second Vatican Council; 2) a network of

sub- or extra- parish communities committed to the same five

characteristics evident in the progressive local churches sketched

above.

This network of Catholic resistance is astonishingly widespread and

persistent. Although rarely existing as an official or entire parish,

it appears in almost every part of the country. There are two main

populations of this network. The first is what has come to be called

“Small Christian Communities.” These groups (SCCs) exist at the edges

of organized Roman Catholicism. Many of them have been started by

regular parish initiatives and continue to consider themselves a part

of those parishes. Some of them have originated through the

initiatives of individuals, a religious order, or an informal action

within an existing parish.

The SCCs gather in small groups. Although some have grown to include

as many as five hundred members, the typical SCC meets in a home or

parish hall and has a constituency under thirty people. About

one-third of SCCs gather weekly and another one-third gather biweekly.

These groups are made up almost entirely of laypeople, although

occasionally a woman religious or—less frequently—a priest will take

part.

When SCCs gather, they typically engage in the following: prayer,

faith sharing, discussion of scripture, spiritual exercises, group

silence, and sharing of visions. Some of them also share eucharist

regularly, sometimes with a priest and sometimes without. Their

leadership is mostly informal, almost always from within the group,

and consistently of a volunteer nature. The members of the group

pledge to support one another in crises. They generally work together

outside their spiritual gatherings on a “mission” project that

addresses a particular social or economic need. Almost half of the

groups engage as a group in a larger advocacy action in society. These

include working for the elimination of poverty, advocacy for human

rights, and protesting social injustice.

Commissioned and funded by the Lilly Foundation in 1996, Bernard Lee,

S.M., of Loyola University in New Orleans and William V. D’Antonio of

the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. directed a

massive team of researchers to study these SCCs. The study produced a

book, The Catholic Experience of Small Christian Communities (Paulist

Press, 2000), that describes and documents these communities, of

which, it estimates, there were 37,895 as of 2000, the year of the

study. Analysis of Lee and D’Antonio’s research reveals that about

half of these—some 19,000 groups—fit the above five characteristics of

progressive Christianity. It is clear then that American Catholicism

has literally hundreds of thousands of active progressive Christians

flying beneath the official radar, and thriving in these small

Christian communities.

The other major population of Catholic resistance is a significant

proportion of American nuns (or, as they prefer to be called, “women

religious”). These women are the one part of the American Roman

Catholic Church that is still working hard to implement the Vatican II

Council’s call in the 1960s to aggiornamento (an Italian term for

“updating” that refers to the task of bringing faith to contemporary

expression). Although one can still find some conservative orders of

women religious, the vast majority have made earthshaking shifts in

their lifestyle, outlook, self-understanding, and appearance. Most

American women religious no longer wear habits and so are almost

invisible to the public. But they are nearly everywhere.

Today the great majority of American women religious live in small

communities. The leadership is rarely hierarchical and governance

tends to be relatively democratic. These women continue to lead

celibate lives, have little or no private property, and pray

communally at least once a day. Their professions vary widely within

the helping professions. It is not unusual for such groups to have

professors, social workers, elementary school teachers, therapists,

and church workers living together with a strikingly simple lifestyle.

The Leadership Council of Women Religious (LCWR) is the national

clearinghouse for this astonishingly strong movement. LCWR provides

major resources for the thousands of communities of women religious

across the country. LCWR’s official self-understanding corresponds in

major ways to what my book portrays as progressive Christianity.

LCWR’s 2004 official declaration of goals for the next five years

starts with the ongoing commitment to vital spirituality, vowing both

to “ground all our actions in contemplation” and to “welcome . . . new

ways of living into the future of religious life.” LCWR, which

represents about 1,000 different orders of women religious in America,

has a strong new focus on environmental consciousness, pledging to

“live and lead rooted in right relationship with all creation.” The

other goals place emphasis on “peacemaking and reconciliation,” the

challenge to “risk being agents of change within our congregations,

our church, and our society,” and working to “stand with those made

poor, particularly women and children.”

Perhaps one of the surest indications that LCWR belongs to the

implicit progressive Christian movement in the past fifteen years is

the strong opposition to it by conservative Catholic organizations.

“Catholic Culture,” a conservative watchdog organization, advises the

public against LCWR’s “radicalization coinciding with the rise of

feminism and the post-Vatican II confusion.” It worries that in 1979

Sister Theresa Kane, then “head of the LCWR” had “chided the pope for

not ordaining women.” This conservative attack on LCWR accuses it of

“antagonism toward the hierarchy and Church teachings,” promoting “the

causes of dissidents,” and being “loaded with liberalism’s

terminology.”

Progressive Christianity is observable in other places. A New

Spiritual Home has chapter-length treatments of two other phenomena:

some similar developments in relatively new denominations like Unity

and the Metropolitan Christian Church and what I call—with gratitude

to Bishop John Spong for part of the term, “the exiles” and their

books. The exiles, as Bishop Spong describes them, by and large do not

belong to a community, but are active in their hope for alternatives,

often through their devotion to a new dose of books over the past

decade, often published by Polebridge Press.

Conclusion

It is my hope that this portrait of emerging progressive Christianity

may interest those disillusioned souls who think that the only

Christian shows going these days are the reactionary evangelicals or

the frightened mainstream institutions. I also wish that those many

different creative, progressive Christians who have courageously

hammered out new ways of being together in the past two decades might

realize that they are not alone. Finally, it seems that the research

this book reports may spark some new regional and national

conversations among progressive churches so that they may emerge more

clearly as the eloquent new national Christian voice they are.

It is clear to me that this new vibrancy at the grass roots will not

become a majority phenomenon in America in any foreseeable future. In

this regard, it seems to me that evangelical Christianity will

continue to play a large role in American Christianity for at least

the next generation. And, even though I suspect that denominational

Christianity has—for better and worse—outlived its usefulness and

attraction for most Americans, it will probably take at least several

decades to die.

Grassroots progressive Christianity is cross-denominational in

character. That is, it is emerging organically from the grass roots

across the country without denominational impulse or charismatic

national leader. Its strength lies in the integrity of its search for

more authentic Christian expression and articulation.

In many ways, this new and widespread impulse can be compared to the

renewal of portions of Christianity in the Dark and Middle Ages

through the establishment and flourishing of monasticism. Monasticism

emerged in Europe as a powerful minority protest against the

corruption, intellectual laziness, and spiritual roteness of the

mainstream institutional churches. The monasteries, abbeys, and

cloisters became innovative expressions of spiritual renewal and

intellectual rigor. They influenced the future of the churches far

beyond their numbers because of their integrity and insight. Today’s

vital grassroots Christianity can also be such a renewing force and

exceptional influence on its culture.

Hal Taussig is Visiting Professor of New Testament at Union

Theological Seminary in New York. He is also co-pastor at the Chestnut

Hill United Methodist Church. His books include A New Spiritual Home:

Progressive Christianity at the Grass Roots (2006), Re-Imagining Life

Together in America (2002), Jesus Before God (1999), Re-Imagining

Christian Origins (1996), and Wisdom’s Feast (1996). He is also a

member of the Jesus Seminar, sponsored by the Westar Institute.

Originally published in The Fourth R, An Advocate for Religious

Literacy, May-June, 2006, Vol. 19, Number 3. The Fourth R is published

by Polebridge Press on behalf of the Westar Institute. For more

information about Westar and it’s publications, programs and research

(including the Jesus Seminar), go to www.westarinstitute.org.

S TRATEGY FOR AN IUCN PRESENCE IN EUROPE DRAFT

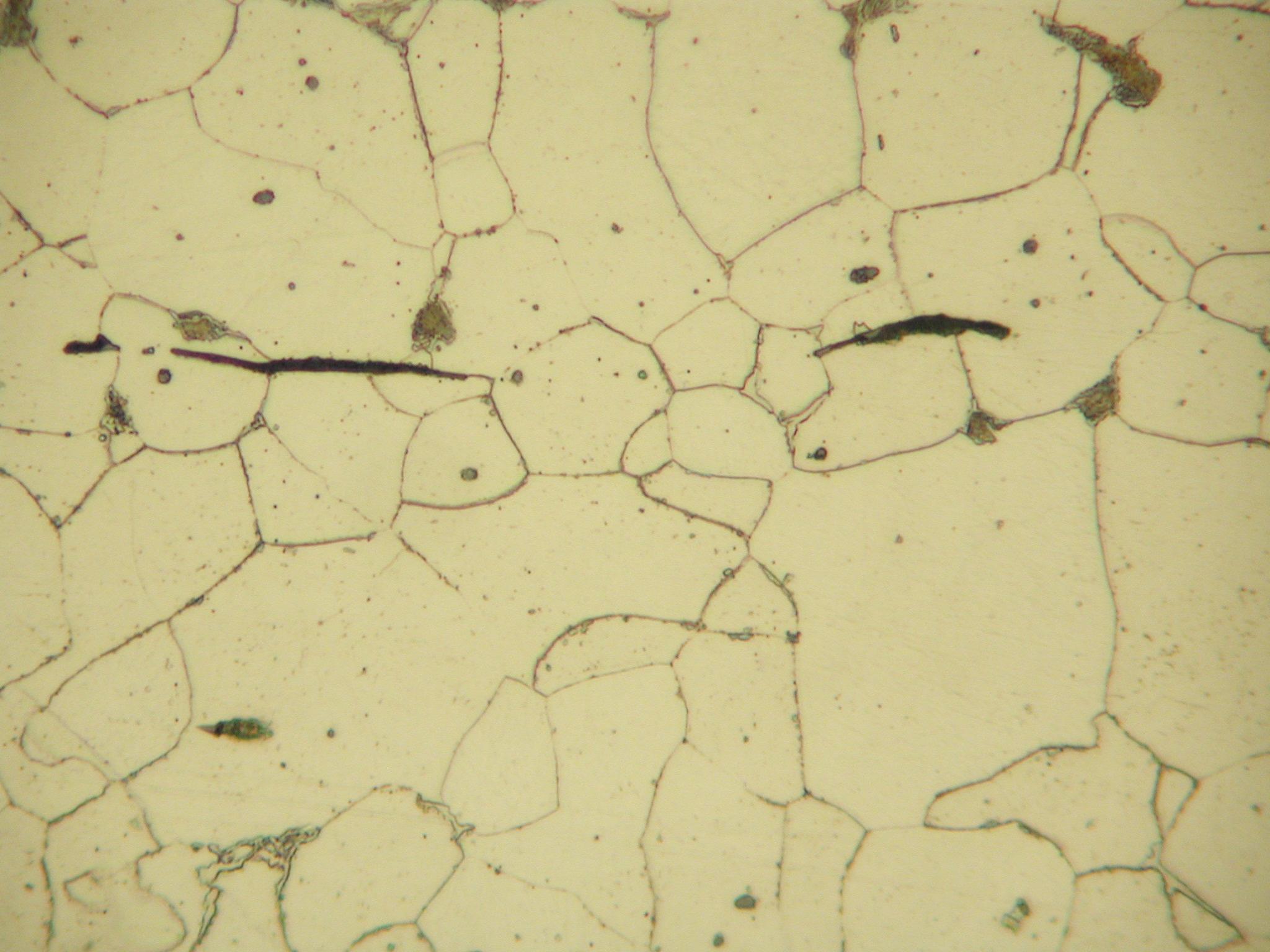

S TRATEGY FOR AN IUCN PRESENCE IN EUROPE DRAFT NAZWISKO I IMIĘ GRUPA DATA ZESPÓŁ OCENA ROK AKADEMICKI

NAZWISKO I IMIĘ GRUPA DATA ZESPÓŁ OCENA ROK AKADEMICKI SMLOUVA O ZAJIŠTĚNÍ ODBORNÉ PRAXE I SMLUVNÍ STRANY

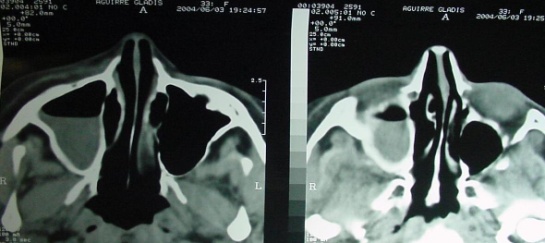

SMLOUVA O ZAJIŠTĚNÍ ODBORNÉ PRAXE I SMLUVNÍ STRANY CIRUGIA DEL SENO MAXILAR OD CAMPAGNALE RAMIRO (ESPECIALISTA EN

CIRUGIA DEL SENO MAXILAR OD CAMPAGNALE RAMIRO (ESPECIALISTA EN WNIOSEK O WYDANIEZMIANĘ UPRAWNIENIA DIAGNOSTY … (MIEJSCOWOŚĆ I

WNIOSEK O WYDANIEZMIANĘ UPRAWNIENIA DIAGNOSTY … (MIEJSCOWOŚĆ I TC SANAYİ VE TİCARET BAKANLIĞI TÜRKİYE SANAYİ STRATEJİSİ BELGESİ

TC SANAYİ VE TİCARET BAKANLIĞI TÜRKİYE SANAYİ STRATEJİSİ BELGESİ WAIKATO BIODIVERSITY FORUM NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2010 NUMBER 28 KIA

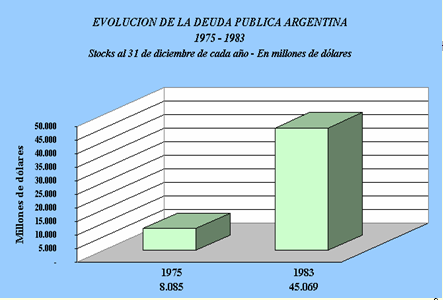

WAIKATO BIODIVERSITY FORUM NEWSLETTER AUGUST 2010 NUMBER 28 KIA EL SISTEMA DE CRÉDITO PÚBLICO LA DEUDA PÚBLICA DE

EL SISTEMA DE CRÉDITO PÚBLICO LA DEUDA PÚBLICA DE DEAR POTENTIAL MENTOR THANK YOU FOR YOUR INTEREST IN

DEAR POTENTIAL MENTOR THANK YOU FOR YOUR INTEREST IN VALSTS VESELĪBAS APDROŠINĀŠANAS KONCEPCIJA I IEVADS AR MINISTRU PREZIDENTA

VALSTS VESELĪBAS APDROŠINĀŠANAS KONCEPCIJA I IEVADS AR MINISTRU PREZIDENTA