matthew arnold the function of criticism / overview / (or preperation or imitation) arnold is a neo-platonist, i.e. he approaches literat

Matthew Arnold

The Function of Criticism / Overview / (or Preperation or Imitation)

Arnold is a Neo-Platonist, i.e. he approaches literature in a platonic

fashion. He believes in an ideal (the creative effort) and a method

through (critical activity) which we can approach this. Critical

activity, then, prepares the way for creative activity. As such,

critical activity is an inferior to the creative. He also believes, as

befits a Platonist, that his ideal should prevail over any inferior

ideas/ideals, i.e. that there is a “best” culture that should

(ideally) drive out the worst.

Arnold (see below) proposes that the critical activity creates an

atmosphere that makes it possible for masterpieces to exist. This

atmosphere consists of “the best ideas.” It is the critic’s job to

bring these ideas forward.

his is one thing to be kept in mind.

92 Another is, that the exercise of the creative power in the

93 production of great works of literature or art, however

94 high this exercise of it may rank, is not at all epochs

95 and under all conditions possible; and that therefore

96 labour may be vainly spent in attempting it, which might

97 with more fruit be used in preparing for it, in rendering

98 it possible. This creative power works with elements,

99 with materials; what if it has not those materials, those

100 elements, ready for its use? In that case it must surely

101 wait till they are ready. Now in literature,--I will limit

102 myself to literature, for it is about literature that the

103 question arises,--the elements with which the creative

104 power works are ideas; the best ideas, on every matter

105 which literature touches, current at the time; at any rate

106 we may lay it down as certain that in modern literature

107 no manifestation of the creative power not working with

108 these can be very important or fruitful. And I say

109 current at the time, not merely accessible at the time;

110 for creative literary genius does not principally show

111 itself in discovering new ideas; that is rather the business

112 of the philosopher; the grand work of literary genius is

113 a work of synthesis and exposition, not of analysis and

114 discovery; its gift lies in the faculty of being happily

115 inspired by a certain intellectual and spiritual atmosphere,

116 by a certain order of ideas, when it finds itself in them;

117 of dealing divinely with these ideas, presenting them in

118 the most effective and attractive combinations, making

119 beautiful works with them, in short. But it must have

120 the atmosphere, it must find itself amidst the order of

121 ideas, in order to work freely; and these it is not so

122 easy to command. This is why great creative epochs

123 in literature are so rare; this is why there is so much

124 that is unsatisfactory in the productions of many men of

125 real genius; because for the creation of a master-work

126 of literature two powers must concur, the power of the

127 man and the power of the moment, and the man is not

128 enough without the moment; the creative power has, for

129 its happy exercise, appointed elements, and those ele-

130 ments are not in its own control.

Arnold Continues

s 31 Nay, they [the creative ideas] are more within the control of the

critical

132 power. It is the business of the critical power, as I said

133 in the words already quoted, " in all branches of know-

134 ledge, theology, philosophy, history, art, science, to see

135 the object as in itself it really is." Thus it tends, at last,

136 to make an intellectual situation of which the creative

137 power can profitably avail itself. It [Criticism] tends to

establish

138 an order of ideas, if not absolutely true, yet true by

139 comparison with that which it displaces; [tends] to make the

140 best ideas prevail. Presently these new ideas reach

141 society, the touch of truth is the touch of life, and there

142 is a stir and growth everywhere; out of this stir and

143 growth come the creative epochs of literature

Therefore, critics and criticism create the conditions for great art.

They do this by identifying the “best ideas” and by making sure that

those ideas “prevail” against inferior ideas. When the best ideas

prevail, then a poet / painter / novelist / filmmaker will be affected

by these ideas and create great art. Arnold contends that it is not

enough to be an artistic genius. You have to live in a moment or epoch

of genius. His examples are the Ancient Greece and the England of

Shakespeare.

…but in the Greece of Pindar and

194 Sophocles, in the England of Shakspeare, the poet lived

195 in a current of ideas in the highest degree animating and

196 nourishing to the creative power; society was, in the

197 fullest measure, permeated by fresh thought, intelligent

198 and alive; and this state of things is the true basis for

199 the creative power's exercise, in this it finds its data, its

200 materials, truly ready for its hand; all the books and

201 reading in the world are only valuable as they are helps

202 to this.

Critics have a large and difficult responsibility in creating this

intellectual atmosphere.

1.

First they have to identify what is best (an essential Platonic

activity)

2.

They have to make sure the best prevails (also essential Platonic

activity)

3.

They do this by attacking what is not the best (ditto)

4.

This is guaranteed not to make them popular (see Socrates) as the

best is not always popular and may, in fact, be decidedly

unpopular

5.

As a result, critics may not be around to see their efforts

succeed either because it will take a long time for the unpopular

best ideas to become assimilated into culture (the theory of

evolution is still being fought in the courts 147 years after it

was announced) OR because the ruling culture will get rid of the

critic by imprisoning her, exiling her, or killing her (See

Socrates—and numerous others)

This raises questions:

1.

What / who defines the “best” in a culture?

2.

How does one go about identifying it? What is the method?

3.

Who knows this method? Where is it taught?

4.

And what qualifies that someone for being an identifier of the

best?

5.

How does one make sure that the best ideas prevail?

6.

What / who gets left out? What happens to them / it?

7.

Why does this matter so much? Is culture that big a deal? Isn’t it

more important to have the right to vote, good health care, and as

much money as possible?

8.

What is the relation of an artist to the culture to which they

belong?

9.

What does it mean to belong to a culture, anyway?

10.

Oh—and what is a culture?

11.

Do artists have any responsibilities to their cultures?

Let’s look at Arnold’s argument.

The English Romantics / Not Knowing Enough / And Reading--And Not

Reading

Let’s look at Arnold’s idea about reading—because a lot of what this

essay is doing has to do with reading: what one should and should not

read and why that matters.

Arnold begins the Function of Criticism (which is an essay) by

referring to an earlier essay he had written On Translating Homer.

This essay had been read by a number of people who took exception to

his remarks in it that English intellectuals don’t want to “see the

object as it really is.” Arnold argued that the intellectuals of

Germany, France, etc. do see (or try to see) the “object”—whatever it

may be—“as it is,” with the result progress of a kind (criticism) is

implied in Germany and France as regards, “theology, philosophy,

history, art, science,” that is not happening in England.

To restate: Arnold begins The Function of Criticism as a response to

the reading that other people had given an earlier essay, On

Translating Homer. Arnold writes. People read. They respond—in

writing. Arnold reads what they write. He writes more. We read that.

Now we, respond. Arnold, alas, cannot write back to us. My point in

pointing out the obvious is that Arnold believes that reading is an

important part of criticism. If culture is a kind of “atmosphere,” a

“current of ideas,” “a national conversation,” then reading (or going

to the movies, to plays, to concerts, to museums, to galleries, to

recitals) and responding to reading (plays, movies, recitals, gallery

shows) is crucial to creating this current, atmosphere, conversation.

Reading and response is the conversation, is the current, is the

atmosphere.

Therefore, what you read matters as does the fact of responding.

Platonically, as it were, one might say that the Function of Criticism

functions as a kind of model, an ideal, an exemplar, of how to create

this atmosphere. Arnold is giving an example in the opening paragraph

(and, really, in the writing of the essay itself, which is one long

response) of the kind of cultural back and forth that he argues for in

The Function of Criticism.

Arnold responds to his readers by first noting that his readers object

to the above remark by saying that the creative effort is greater than

that of critical. In short, that is better to do something than to

criticize something or to criticize someone else for what they did.

Arnold then produces the example of the Romantic poet, Wordsworth. He

quotes Wordsworth:

The writers in these publications" (the Reviews),

28 "while they prosecute their inglorious employment, can-

29 not be supposed to be in a state of mind very favour-

30 able for being affected by the finer influences of a thing

31 so pure as genuine poetry."

32 And a trustworthy reporter of his conversation quotes

33 a more elaborate judgment to the same effect:--

34 "Wordsworth holds the critical power very low, in-

35 finitely lower than the inventive and he said to-day

36 that if the quantity of time consumed in writing critiques

37 on the works of others were given to original com-

38 position, of whatever kind it might be, it would be

39 much better employed; it would make a man find out

40 sooner his own level, and it would do infinitely less

41 mischief. A false or malicious criticism may do much

42 injury to the minds of others; a stupid invention, either

43 in prose or verse, is quite harmless

Arnold then goes onto say that Wordsworth, asking a question:

is it certain that Wordsworth himself was better

63 employed in making his Ecclesiastical Sonnets, than

64 when he made his celebrated Preface, so full of criticism,

65 and criticism of the works of others? Wordsworth was

66 himself a great critic, and it is to be sincerely regretted

67 that he has not left us more criticism; Goethe was one

68 of the greatest of critics, and we may sincerely congratu-

69 late ourselves that he has left us so much criticism.

That is to say: Wordsworth’s poetry sometimes suffered from a lack of

critical spirit.

Arnold then admits that yes, that creative activity is a greater

activity than criticism. But, Arnold then goes on to say

In other words, the English poetry of the

172 first quarter of this century, with plenty of energy, plenty

173 of creative force, did not know enough. This makes

174 Byron so empty of matter, Shelley so incoherent, Words-

175 worth even, profound as he is, yet so wanting in com-

176 pleteness and variety. Wordsworth cared little for books,

177 and disparaged Goethe. I admire Wordsworth, as he is,

178 so much that I cannot wish him different; and it is vain,

179 no doubt, to imagine such a man different from what he

180 is, to suppose that he could have been different; but

181 surely the one thing wanting to make Wordsworth an

182 even greater poet than he is,--his thought richer, and his

183 influence of wider application,--was that he should have

184 read more books, among them, no doubt, those of that

185 Goethe whom he disparaged without reading him.

Then, Arnold backpedals a bit. After all:

But to speak of books and reading may easily lead to

187 a misunderstanding here. It was not really books and

188 reading that lacked to our poetry, at this epoch; Shelley

189 had plenty of reading, Coleridge had immense reading.

190 Pindar and Sophocles,--as we all say so glibly, and often

191 with so little discernment of the real import of what we

192 are saying,--had not many books; Shakspeare was no

193 deep reader. True; but in the Greece of Pindar and

194 Sophocles, in the England of Shakspeare, the poet lived

195 in a current of ideas in the highest degree animating and

196 nourishing to the creative power; society was, in the

197 fullest measure, permeated by fresh thought, intelligent

198 and alive; and this state of things is the true basis for

199 the creative power's exercise, in this it finds its data, its

200 materials, truly ready for its hand; all the books and

201 reading in the world are only valuable as they are helps

202 to this.

In other words, individual reading can only take someone so far. The

culture the artist lives in must be “permeated by fresh thought.” But,

how is it that a culture becomes permeated by fresh thought?

Shakespeare did not have to read because others did, i.e. others

traveled, others translated, people talked, debated, things changed—or

didn’t—and Shakespeare was in the middle of all that reading,

traveling, talking, debating, arguing, reading a bit himself (he

obviously read Plutarch’s Lives) and writing a lot and being a hugely

talented genius. Many people read, Arnold would argue, in order that

Shakespeare might write.

Arnold goes on to argue that even if a culture such as Shakespeare’s

does not exist for an individual (we can’t all live in Elizabethan

England)

Even when this does not actually exist, books

203 and reading may enable a man to construct a kind of

204 semblance of it in his own mind, a world of knowledge

205 and intelligence in which he may live and work; this is

206 by no means an equivalent, to the artist, for the nationally

207 diffused life and thought of the epochs of Sophocles or

208 Shakspeare, but, besides that it [reading and books] may be a

means of

209 preparation for such epochs, it does really constitute, if

210 many share in it, a quickening and sustaining atmosphere

211 of great value. Such an atmosphere the many-sided

212 learning and the long and widely-combined critical effort

213 of Germany formed for Goethe, when he lived and

214 worked. There was no national glow of life and thought

215 there, as in the Athens of Pericles, or the England of

216 Elizabeth. That was the poet's weakness. But there

217 was a sort of equivalent for it in the complete culture and

218 unfettered thinking of a large body of Germans. That

219 was his strength. In the England of the first quarter of

220 this century, there was neither a national glow of life and

221 thought, such as we had in the age of Elizabeth, nor yet

222 a culture and a force of learning and criticism, such as

223 were to be found in Germany. Therefore the creative

224 power of poetry wanted, for success in the highest sense,

225 materials and a basis; a thorough interpretation of the

226 world was necessarily denied to it.

So…reading may construct a semblance (a kind of imitation) of, if you

will, the conditions of the Renaissance, a semblance (imitation) of a

“world of knowledge and intelligence,” in a person’s “own mind,” where

he can “live and work.”

So reading creates an imitation Renaissance where a person can lead a

double life in their mind (no matter what sort of life they lead in

the real world).

But, Arnold reminds us, reading is no substitute/equivalent/double to

the artist of the “real” Renaissance world

Yet, reading is a preparation for this real world (i.e. a dim copy of

the Renaissance to come) and if enough people read, reading may create

an “atmosphere” (a better copy / prophecy of the Renaissance-to-come),

this atmosphere may become “a sort of equivalent for” the

Renaissance-to-come, and, hey, you have Goethe, who functions a bit

like a Shakespeare analog for Germany.

English Romantic poets did not have this atmosphere of reading, thus

their poetry was weak in comparison to Goethe.

So you have this chain of metaphors: Reading =semblance=private world

of knowledge=preparation=public atmosphere=equivalent

In short, if a certain kind of reading (and response to reading)

reproduces itself—is viral as would say today—fast enough, deep enough

in a culture—this mass reproduction becomes an atmosphere or current

of ideas. Then, artists responding to the current, start making

masterpieces (maybe).

But it has to be the right sort of (the best) reading/response.

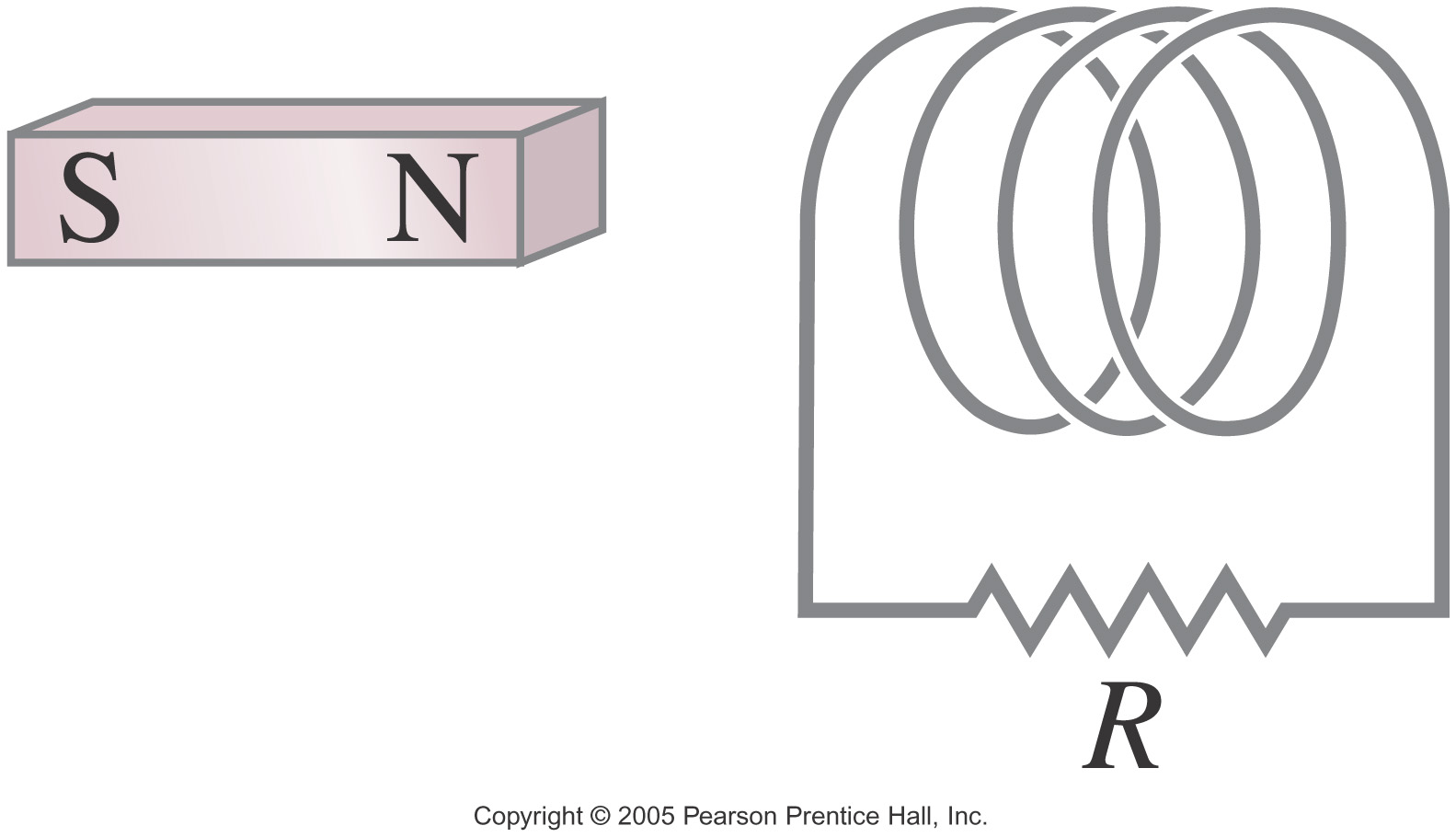

So Arnold imagines a process something like the image below.

One of a criticism’s jobs, then, is to encourage the right kind of

reading, the right kind of attention to the right sort of movie,

dance, theater, music, opera, you-name-it.

What’s Wrong with the French Revolution?

You probably noticed that Arnold spent a great deal of time talking

about the French Revolution. Why? The era of the French Revolution

(and the American Revolution before it) would seem to be the sort of

period in which a “current of ideas” or “atmosphere” that Arnold

means. Both revolutions were if nothing else, revolutions about

ideas—namely ideas about who rules whom, why, and how, and for how

long. Both revolutions created an immense amount of intellectual work.

On our side: Common Sense, The Declaration of Independence, The

Constitution of the United States, The Federalist Papers, the

Anti-Federalist Papers, as well as hundreds (thousands?) of pamphlets,

speeches, newspaper editorials, etc. The same was true of France. Over

the course of the late 17th and 18th century, Montesquieu, Voltaire,

Diderot, and many others wrote essays, books, articles, etc. that

challenged the idea of the rule of the nobility. 1 The French

Revolution itself produced a mass of justifications for its actions in

the form of pamphlets, essays, etc. So lots of ideas, lots of writing,

lots of reading, and some pretty dramatic “response” to the reading

(the Revolution). That’s why Arnold says it’s strange no masterpieces

came out of the French Revolution….

At first sight it seems strange that out of the immense

228 stir of the French Revolution and its age should not

229 have come a crop of works of genius equal to that which

230 came out of the stir of the great productive time of

231 Greece, or out of that of the Renaissance, with its

232 powerful episode the Reformation. But the truth is that

233 the stir of the French Revolution took a character which

234 essentially distinguished it from such movements as these.

235 These were, in the main, disinterestedly intellectual and

236 spiritual movements; movements in which the human

237 spirit looked for its satisfaction in itself and in the in-

238 creased play of its own activity: the French Revolution

239 took a political, practical character.

According to Arnold the French Revolution made an error: it tried to

put theory into practice via politics, i.e. cutting off the king’s

head (and a great many other heads besides). For their part

Shakespeare and Co were content to absorb the spirit of the age and

keep it on the stage and out of the streets. As Sister Thomas Hoctor

S.S.J. points out in her introduction to Arnold’s Essays in Criticism,

“disinterestedness” is one of the key elements of Arnold’s theory of

criticism.

Recall that Arnold says that it is the duty of criticism to see “the

object as it really is.” If you are to do that, to see something as

“really is,” (if that is possible—but let’s assume for the moment that

it is possible), then you need to be careful not to see an object (or

a person) for what they are to you. For example: If one needs a ride

somewhere, one may tend to see people not as complex individuals

seeking happiness in their own ways for their own ends and doing so in

a limited world in a limited time using their limited resources.

Rather one (you, me) tends to reduce people (for the moment) to

sources for a ride home and may tend to manipulate people to that end.

“If you give me a ride to the party, say, I will be your friend at the

party and introduce you to everyone. If not, not.” Most people

wouldn’t be quite that blunt, but such promises can be tacitly made.

Arnold would argue that the same thing is true of ideas, even the

so-called “best ideas.” Take the idea of democracy, i.e. rule by the

will of the majority. It’s a good idea, but if put into practice, then

it gets messy. People start forming political parties. Parties have

agendas. Agendas are not about disinterest. They are entirely about

interest. Next thing you know, the Bastille is exploding or workers

are demanding their rights. It’s better to write poems, plays, make

movies, etc. read the poems, watch the movies, and argue about

democracy. Try to see what democracy is in itself. Then, one day, if

enough people are convinced, if the goodness of democracy becomes

self-evident, democracy happens. Arnold essentially, says, that

democracy would have happened eventually because it appeals to “an

order of ideas which are universal, certain, permanent,” but the

French revolutionaries forced democracy before France was ready for it

and, so, the guillotine.

250 The French Revolution, however,--that object of so

251 much blind love and so much blind hatred,--found

252 undoubtedly its motive-power in the intelligence of men

253 and not in their practical sense;--this is what distinguishes

254 it from the English Revolution of Charles the First's time;

255 this is what makes it a more spiritual event than our Re-

256 volution, an event of much more powerful and world-wide

257 interest, though practically less successful;--it appeals to

258 an order of ideas which are universal, certain, permanent.

259 1789 asked of a thing, Is it rational?

But the mania for giving an immediate political and

301 practical application to all these fine ideas of the reason

302 was fatal. Here an Englishman is in his element: on

303 this theme we can all go on for hours. And all we are in

304 the habit of saying on it has undoubtedly a great deal

305 of truth. Ideas cannot be too much prized in and for

306 themselves, cannot be too much lived with; but to

307 transport them abruptly into the world of politics and

308 practice, violently to revolutionise this world to their

309 bidding,--that is quite another thing. There is the world

310 of ideas and there is the world of practice;

339 This was the grand error of the French Revolution, and

340 its movement of ideas, by quitting the intellectual sphere

341 and rushing furiously into the political sphere, ran, in-

342 deed, a prodigious and memorable course, but produced

343 no such intellectual fruit as the movement of ideas of

344 the Renaissance, and created, in opposition to itself, what

345 I may call an epoch of concentration.

Arnold is saying that the French Revolution instead of causing an era

of expansion in the intellectual and artistic worlds (as the

Renaissance supposedly did), it created the opposite, “concentration.”

What we would call today, “reaction.” Fear of the French Revolution

caused England to go into intellectual defensive mode, looking /

thinking / reading inward (in a movement that today we would call

“nationalism”) instead of looking outward for the best in

ideas—wherever they may be found. Art and the criticism of art, exists

in a separate cultural sphere, an idealized space, a Platonic space,

where the right people can come into contact with the right ideas at

the right time.

You have to take Arnold’s word for the notion that the French

Revolution bore no intellectual fruit. French art (Impressionism, Post

Impressionism) and French literature (Baudlier, Hugo, Balzac, Rimbaud,

Mallarme, Nerval, the list goes on and on) of the 19th century are

well regarded today. Indeed, Paris was considered the intellectual, if

not financial, capital of Europe till after World War II (when New

York City took the prize).

What’s wrong with Bishop Colenso?

You will recall that Arnold comes down pretty hard on Bishop Colenso,

the Bishop of Natal, a province of the British Empire in what is now

South Africa. Bishop Colenso was translating the Bible into Zulu and

in the process came to the conclusion that the first five books of the

Bible, the Pentateuch, were not literally true. He came to this

conclusion because of internal logical problems in the narrative. He

published his conclusions. This caused a tremendous uproar because

well, the Bishop of Natal, (one of the guardians of the British Empire

if you want to think of him in a Platonic sense), was supposed to

believe (had taken an oath affirming his belief) and to encourage

others to believe in the literal truth of the Bible.

Arnold has no trouble with the Bible not being literally true. This is

old news. That is one of his criticisms of Colenso. The German and

French critics of the Bible long ago showed that anyone who knew

anything about the Bible knew it couldn’t be literally true and they

did so in a smarter way. In other words, Colenso may have spoke the

truth, but he spoke it badly.

What is this? here

799 a liberal attacking a liberal. Do not you belong to

800 the movement? are not you a friend of truth? Is not

801 Bishop Colenso in pursuit of truth? then speak with

802 proper respect of his book. |Dr.| Stanley is another friend

803 of truth, and you speak with proper respect of his book;

804 why make these invidious differences? both books are

805 excellent, admirable, liberal; Bishop Colenso's perhaps

806 the most so, because it is the boldest, and will have the

807 best practical consequences for the liberal cause. Do

808 you want to encourage to the attack of a brother liberal

809 his, and your, and our implacable enemies, the Church

810 and State Review or the Record,--the High Church

811 rhinoceros and the Evangelical hyæna? Be silent,

812 therefore; or rather speak, speak as loud as ever you can,

813 and go into ecstasies over the eighty and odd pigeons."

814 But criticism cannot follow this coarse and indiscriminate

815 method. It is unfortunately possible for a man in pur-

816 suit of truth to write a book which reposes upon a false

817 conception. Even the practical consequences of a book

818 are to genuine criticism no recommendation of it, if the

819 book is, in the highest sense, blundering.

If you read Arnold’s essay, The Bishop and the Philosopher, you find

out that Arnold’s larger problem with Colenso was perhaps that Colenso

told the truth about the Bible too soon. The people, it seems, are not

ready for the truth about the Bible. (see handouts). If they are not

given the truth in the right way by the right sorts, it may lead to a

disturbance like the French Revolution.

But Arnold’s idea that critics and artists should be disinterested as

regards politics and practical affairs—that art occupies, or ought to,

a separate cultural sphere—and that the goal of criticism is, or ought

to be, the cultivation of (for lack of a better term) a superior

culture, is a hugely powerful idea and one that lives on. People,

especially artists, are supposed to take inspiration from criticism.

Criticism must be left alone to do its work. It simply cannot care

about the practical outcomes of its ideas. It’s only criterion is: is

the best idea?

Criticism must maintain its

931 independence of the practical spirit and its aims. Even

932 with well-meant efforts of the practical spirit it must

933 express dissatisfaction, if in the sphere of the ideal they

934 seem impoverishing and limiting. It must not hurry on

935 to the goal because of its practical importance. It must

936 be patient, and know how to wait; and flexible, and

937 know how to attach itself to things and how to withdraw

938 from them. It must be apt to study and praise elements

939 that for the fulness of spiritual perfection are wanted,

940 even though they belong to a power which in the prac-

941 tical sphere may be maleficent. It must be apt to discern

942 the spiritual shortcomings or illusions of powers that in

943 the practical sphere may be beneficent. And this with-

944 out any notion of favouring or injuring, in the practical

945 sphere, one power or the other; without any notion of

946 playing off, in this sphere, one power against the other.

1011 If I have insisted so much on the course which

1012 criticism must take where politics and religion are con-

1013 cemed, it is because, where these burning matters are

1014 in question, it is most likely to go astray. In general,

1015 its course is determined for it by the idea which is the

1016 law of its being; the idea of a disinterested endeavour

1017 to learn and propagate the best that is known and

1018 thought in the world, and thus to establish a current

1019 of fresh and true ideas

1 Ironically, the French king (or his ministers) was decisive in our

winning the American Revolution.

E M W04 WELFARECD CENTRE REPORT (SEE OVER

E M W04 WELFARECD CENTRE REPORT (SEE OVER UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA ECOTEC FACULTAD DE SISTEMAS COMPUTACIONALES Y TELECOMUNICACIONES

UNIVERSIDAD TECNOLÓGICA ECOTEC FACULTAD DE SISTEMAS COMPUTACIONALES Y TELECOMUNICACIONES QUALIFICACIÓ DEPARTAMENT DE CIÈNCIES EXPERIMENTALS PRÀCTIQUES DE

QUALIFICACIÓ DEPARTAMENT DE CIÈNCIES EXPERIMENTALS PRÀCTIQUES DE FAMILY PLANNING SERVICES CONFIDENTIAL & AFFORDABLE THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

FAMILY PLANNING SERVICES CONFIDENTIAL & AFFORDABLE THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT SOLICITUD CERTIFICACION PROCESOS O SERVICIOS (ESQUEMA 6) 1 DATOS

SOLICITUD CERTIFICACION PROCESOS O SERVICIOS (ESQUEMA 6) 1 DATOS STR VĂLENI NR 1 BL 33I33K PARTER PLOIEȘTI PRAHOVA

STR VĂLENI NR 1 BL 33I33K PARTER PLOIEȘTI PRAHOVA DESCRIPTIF DE POSTE COORDINATEUR GENERAL EXPERT SANTÉ PUBLIQUE

DESCRIPTIF DE POSTE COORDINATEUR GENERAL EXPERT SANTÉ PUBLIQUE HOMEWORK 8 CH21 P 3 9 15 23 41

HOMEWORK 8 CH21 P 3 9 15 23 41