seller pricing strategies: a buyer’s perspective by david v. lamm and lawrence c. vose david v. lamm is associate professor of

Seller Pricing

Strategies:

A Buyer’s

Perspective

By David V. Lamm and Lawrence C. Vose

David V. Lamm is Associate Professor of Administrative Sciences at the

Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. He specializes in

the fields of acquisition, contracting, project management, and

logistics. Dr. Lamm earned his D.B.A. degree at the George Washington

University.

Lawrence C. Vose is currently on active duty in the Coast Guard. He

holds an M.S. degree in management from the Naval Postgraduate School.

Lieutenant Vose’s principal specialty is acquisition and contracting

management.

Understanding pricing strategies used by sellers is extremely

important to a successful buyer. Several key variables can be

identified and evaluated in determining the seller’s pricing strategy

and the conditions under which it was developed. Knowing how to

recognize these variables and integrate them into the buying process

Is a challenging and demanding effort. The motivated buyer constantly

hones his or her skills In this area, attempting to obtain the most

advantageous business arrangement for the organization.

This article Identifies various seller pricing strategies and the

principal variables involved in their analysis. The strategies and

variables examined should significantly assist buyers in preparing for

the buying task.

In the institutional, industrial, and governmental buying process,

successful contract negotiation requires knowledge and understanding

of several key elements. The seller’s pricing strategy is one of

these. A perceptive buyer continually explores the factors that

contribute to the development of a seller’s pricing strategy, in an

effort to determine what he or she might do differently by

understanding the strategy.

In preparing for contract negotiations, many buyers typically devote

only modest attention to this area because it is one of the most

difficult in which to obtain valid data. It involves confidential and

proprietary management information. Regardless of the difficulty,

effective buyers must be aware of the types of pricing strategies

sellers are likely to employ, the conditions under which these

strategies generally surface, and the significance of this knowledge

in the buying process. This article identifies some of the more common

pricing strategies and the principal variables that contribute to the

development of the strategy. It concludes with an analysis of the

usefulness of this information to the buyer.

PRICING STRATEGIES

------------------

Copyright November 1988 by thew National Association of Purchasing

Management, Inc.

Pricing strategies exist because, for many hidden as well as obvious

reasons, a seller’s quoted prices are often very dif-

ferent from the prices it actually gets. The following approaches are

commonly used in determining price:

*

Cost-Plus (Penetration) Pricing

*

Demand (Skimming) Pricing

*

Rule-of-Thumb (Myopic) Pricing

*

Buy-in (Foot-in-the-Door) Pricing

Cost-Plus pricing has appeal because it is a logical way to determine

a minimum acceptable price. Although cost is not always a good direct

determinant of price, firms must price their products at a level that

at least recovers operating costs over time.’ This takes on special

significance in new product pricing where a variation known as

“penetration pricing strategy” is used. Greer defines penetration

pricing as a method to diffuse the appeal of the product rapidly

through low initial pricing; then, once the market is “penetrated” to

take ad-vantage of cost reductions and/or price increases to generate

profits.2 This strategy is also aimed at discouraging would-be

competitors from entering the market due to apparently low profit

margins. The buyer’s problem becomes one of determining what cost the

seller is using to price the product.

Demand pricing can be viewed as “charging as much as the market will

bear.” It is based on economic theory which focuses on the concept of

the industry and the finn’s demand curves. A variation of this

strategy, applicable to the introduction of new technology or

innovation in the marketplace, is known as “skimming the cream.”3 The

“skimming” strategy involves high initial pricing in an attempt to

achieve an almost instantaneous return on investment.4 The obvious

risks are that the seller invites competition, that it may not be able

to sell as much as it would like at a high price, and that it may

alienate potential buyers by the apparent profiteering.

Rule-of-Thumb pricing is a middle of the road pricing strategy. Two

general approaches to this strategy include: (1) a leader-follower

concept, allowing competitors to set prices and then following suit,

and (2) a more traditional pricing formula such as direct material and

labor costs plus 40 percent. It is generally considered conservative

and safe by those who use it, often because it has worked in the past.

The Rule-of-Thumb approach greatly simplifies the pricing problem. It

is a way of coping with (by essentially ignoring) uncertainties in the

estimation of demand function shapes and elasticities.5 For the buyer,

it may be much easier to understand and to apply.

The “Buy-In” strategy is a short-term approach based on other than

normal cost recovery or profit motives. It involves pricing to recover

variable costs and perhaps some fixed costs to the extent that a low

enough price is offered to beat the competition. In a different form,

this strategy meets the conditions of a depressed market. One analyst

states that “companies neither record nor generally talk about all the

‘under the table’ prices and other valuable concessions they make when

the market is sluggish.”6 Normal business practice finds

a seller cuffing a deal with a buyer at a “certain” price because of

“certain” conditions. If it became public, other buyers would want

deals similar to this most favored customer regardless of the economic

or financial health of the seller. The relationship between cost data

and pricing decisions on a pragmatic level has received very little

attention as far as empirical research is concerned. This is not

surprising in that it concerns very sensitive questions that firms are

generally unwilling to answer.7

PRICING VARIABLES

Sellers consider many factors in determining a pricing strategy. One

useful approach categorizes these as intrinsic and extrinsic factors.8

Intrinsic factors are the baseline needs, such as costs, product

characteristics, and soon, and the regulatory system which places

limitations on how those needs can be met.9 Extrinsic factors are

related to the economic and operating environment of a procurement,

including product differentiation, demand, and the number of firms

involved.10

The following discussion explores what are considered to be the most

identifiable and significant variables that contribute to a seller’s

pricing strategy in terms of both external and internal variables.

External Variables

Variables in this category can be grouped as: (1) the nature of the

product, (2) market characteristics, and (3) the buyer’s control

variables.

Nature of the product. The most significant aspects of this element of

pricing strategy are the maturity, or stage of the product in its life

cycle, and the degree of differentiation inherent in the product.

Pioneering products offer a much greater flexibility in pricing

strategy than do products in their prime or beyond. The implications

are that a buyer can expect a higher probability of the existence of a

demand (skimming) pricing strategy because of the lack of competition,

the lack of product cost history, and other similar factors that

accompany new product introduction.

The degree of innovativeness or differentiation can be very

significant, assuming that a seller in fact is distinguished from

competitors and that this differentiation is aligned with a buyer’s

desires. Technological innovation may lead to significant cost

advantages and the opportunity for a penetration strategy in cases

where a seller capitalizes on the opportunity to deter the entry of

competitors. On the other hand, a buyer might anticipate a skimming

strategy if a particular product attribute is able to command a

premium price well above the marginal cost of providing it. Other

controlling elements are differential advantages in (1) quality and

superiority—the degree to which a seller markets products that meet

customer needs better than competing products; (2) customer impact and

features—products that have a major impact on buyer

behavior, allow buyer cost reductions, and offer unique features; and

(3) product fit and focus—the degree to which a seller’s products are

similar to existing products in use, have similar end uses, fit in an

existing product line, and are closely related to each other.

The scarcity of a needed product or material may also influence

pricing strategy significantly. For example, a buyer might require a

product using a scarce material that is subject to fluctuations in

price and availability. The buyer should be very cautious if he or she

detects a selling strategy that doesn’t reflect how that scarcity will

affect delivery and performance. The degree to which technology and

R&D are invested in a particular product will often influence the

pricing decision. This is distinct from the innovativeness described

above. A seller in an industry on the leading edge of technology,

characterized by rapid product obsolescence, will tend to employ a

strategy designed to recover investments as quickly as possible.

Depending on the actual volatility of product life, this may or may

not be appropriate from the buyer’s point of view.

Seller’s market characteristics. Many consider these the dominant

variables in the pricing strategy process.11 Seller market structure

involves the application of microeconomic theory, with the primary

emphasis on the nature and degree of competition. Most economists

describe market structure and seller behavior in terms of four types

of competition— perfect competition, monopolistic competition,

oligopoly, and monopoly. The important distinctions among them are the

relationship of the seller’s price and long run average cost, and the

degree of choice the seller has in establishing price. Typically, a

seller in a perfectly competitive market is a price taker (one

extreme), while the firm in a monopolistic position is a price setter

(the other extreme). The key implications for a buyer are that sellers

operating in the first two types of competitive situations will tend

to employ penetration pricing strategies, whereas oligopolistic or

monopolistic sellers have a greater potential to utilize a skimming

strategy.

Closely related to market structure is the nature of product demand

and elasticity. Some theoreticians believe that the most influential

concept in seller pricing behavior is that of demand elasticity

relative to price.’2 That is, the degree to which buyers’ aggregate

demand for a given product will change as the price is set at higher

or lower levels. A product is said to have an elastic demand if

aggregate demand drops off as the price increases. Practically

speaking, the relevant feature of demand elasticity for a buyer is

that selling firms frequently believe the demand for their product is

much more elastic than is truly the case.13

Other seller market characteristics include things such as competitive

loyalty, market newness, and market segmentation. Competitive loyalty

focuses primarily on establishing and maintaining a long-term

relationship between buyer and seller. The pricing approach utilized

typically is consistent with this objective and involves some form of

cost plus a

“fair” profit return determination. Market newness exploits the

differences between fresh and existing markets, frequently creating

distinctly different pricing strategies. The effect of market

segmentation is the ability to sell to buyers in different markets at

different prices, with no significant repercussions. What really

determines segmentation sensitivity is not the number and similarity

of available substitutes but individual buyer’s perceptions about

these things.14 If a selling firm believes that a buyer may not be

aware of competing products or substitutes, it may be inclined to

increase the profit margin.

The state of the national economy and the extent of industry capacity

utilization at a given time are also influential factors in price

determination. Overcapacity frequently leads to dramatic price

reductions, particularly in capital-intensive industries experiencing

keen competition.15 In such cases, a buyer should expect to see more

cost-plus pricing and should be alert for “buy-in” strategies.

Buyer’s control variables. These factors are unique in the

government-commercial procurement relationship. Most government

procurement is conducted with the buyer functioning in the role of a

monopsony. There are several differences between private and

government procurement that may affect the seller’s pricing strategy.

The most significant of these are the status of parties,

accountability, and process complexity.16 The effect of these

differences is difficult to quantify; however, experience indicates

that the number of hurdles a seller must clear in government

procurement may force that seller’s pricing strategy away from the

penetration approach. The unsteadying influence of the political

process on government programs impacts the seller’s assessment of risk

and long-term relationships. In such a situation, a buyer might expect

either skimming or buy-in pricing.

The type of contract utilized in government procurement will have a

significant impact on a seller’s pricing strategy. Cost reimbursement

contracts encourage the overoptimistic estimation of costs and a

resultant buy-in strategy (particularly in research and development

efforts), while fixed-price contracts tend to promote the

rule-of-thumb or skimming strategy. The implication for a government

buyer is that under a fixed-price contract, the seller attempting to

use a buy-in strategy may be in a difficult position should

performance problems develop. Government buyers may encounter greater

usage of the skimming strategy in the fixed-price contract situation

as the seller evaluates the degree of risk it must assume.

Internal Variables

Variables in this category can be grouped as (1) seller’s internal

characteristics, (2) management orientation, and (3) accounting and

costing methods.

Seller’s internal characteristics. A seller’s current capacity

utilization factor is one of the most significant elements affecting

its pricing strategy. At times, this situation may be tied closely to

the industry and national economic conditions

on the external side. If a seller is operating at or near 100 percent

capacity, it may be able to extract a substantial profit to displace

existing business. Conversely, in periods of underutilized capacity, a

seller’s emphasis shifts from a profit motive to the recovery of fixed

costs and the continued employment of resources. Hence, a buyer can

expect an increased occurrence of buy-in and penetration strategies

when a seller has excess capacity, and a skimming strategy in periods

of full capacity utilization.

A selling firm’s general financial health is another factor that can

influence its pricing strategy. A financially sound seller may use a

buy-in strategy less often than a firm that is financially less

stable. Some observers have noted that turnover and liquidity seem to

be the most important dimensions of financial condition from the

standpoint of bankruptcy. In such cases, profitability clearly is the

factor of least immediate importance.17

The degree to which a firm can control its costs dictates the range of

pricing strategies available. Efficient operation allows a seller to

profitably use a penetration strategy under many circumstances.

Efficiencies often result from economies of scale and from prior job

experience. Economies of scale often are available more frequently to

the larger more oligopolistic selling organizations. In these types of

organizations, economies of scale sometimes are used to create a

barrier to market entry. As such, they may permit the seller to

exercise a wider range of pricing strategies than would otherwise be

possible.

Economies stemming from prior job experience frequently are visible in

the form of a learning or improvement curve. Greer has identified a

relationship between the slope of a firm’s learning curve and the

particular pricing strategy employed for major airframe manufacturers.18

He has correlated a steeper sloped curve with a skimming strategy and

a flatter curve with the penetration strategy. In such procurement

situations, it appears the buyer may have a fairly definitive

indicator of the seller’s pricing strategy.

The nature of a seller’s costs and the type of business also influence

its pricing strategy. A firm with heavy capital investment often can

produce at relatively low variable costs per unit. An understanding of

a seller’s capital structure can provide valuable insights into the

particular pricing strategy the seller is employing. For a firm with a

high cost of capital, the type of contract contemplated can combine to

significantly influence the strategy pursued. Likewise, a firm that

basically is an assembler rather than a manufacturer may not be able

to predict its costs accurately due to increased reliance on

subcontractors. Clearly, this situation will influence the pricing

process.

Management orientation. Management objectives, such as sales targets,

target levels of employment, designated rate of return, and the

preference for risk avoidance, all affect pricing strategies.

The initial influence of a seller’s management orientation is revealed

in the firm’s interest in obtaining contract work. Some sellers are

willing to accept new business only if the rate of return is

substantial enough to compensate them for any added risks and

requirements. Others emphasize repeat business. The importance of

repeat business is directly related to perceived market stability. If

top management feels that a certain type of business activity as a

regular percentage of the contract base is necessary, the pricing

strategy will be adjusted to ensure a higher probability of success in

obtaining such contracts. The pricing strategy will reflect

management’s estimated probability of winning the award, the value it

places on the work, and the cost of not getting the contract in terms

of employment, contribution margin, com-petitors’ advantage, and total

sales volume. Inherent in this element is management’s stated

objectives of cost recovery, profit, and capital employment.

Accounting and costing methods. The more a buyer knows about a

seller’s internal accounting system, the greater will be his or her

ability to diagnose the seller’s pricing strategy. For example, the

depreciation of tangible assets by a seller can have significant

impact on the firm’s stated operating costs. An accelerated method of

depreciation will produce higher costs early in a product’s life

cycle. Similarly, the use of LIFO (last in, first out) inventory

accounting in a period of rising costs will result in the earlier

recognition of costs. The use of full absorption costing obscures what

it actually costs a firm to produce on the margin. At the same time,

however, the true nature of a seller’s costs may be hidden from its

competitors.

The significance of these considerations to a buyer is that the

accounting method used in reporting cost data may not be the

accounting method the pricing strategy is based on. Closely related to

the seller’s accounting for costs is the method the seller uses to

estimate future costs. The validity of a seller’s cost estimating

relationships will affect the perception of expected costs and

therefore influence the strategy to price for cost recovery.

CHALLENGES FOR THE BUYER

Four common pricing strategies and the key variables to be considered

in evaluating these strategies have been identified. The understanding

that comes from the process of trying to determine a seller’s pricing

strategy will significantly assist a buyer in his or her effort to

obtain fair and reasonable prices. An analysis of the factors and the

conditions involved in a particular buy will contribute to the

preparation so necessary to successful contract negotiation.

In examining the potential pricing methods a seller might use, buyers

must place themselves in the “seller’s shoes” and attempt to evaluate

the relative significance of both external and internal variables.

They should ask themselves,

What pricing approach is most likely to fulfill the objectives and the

needs of the seller, given the economic structure and the extent of

competition found in its industry?” This requires the buyer to make an

assessment of the seller’s objectives and needs to sufficiently

understand the motivations and incentives involved. For example, at

the present time a seller may not be motivated by profit maximization

on a given contract, but rather may be seeking an expansion of its

sales volume and is employing a pricing strategy that recognizes this

need.

Of the four pricing strategies, penetration (cost-plus) pricing and

rule-of-thumb pricing are perhaps the easiest for a buyer to

understand and to deal with. They are also the strategies in which

sellers are willing to divulge how costs were estimated and to provide

data supporting these estimates. Skimming and buy-in pricing are

difficult to detect and even more difficult to counter. Sellers

typically are unwilling to admit such strategies have been used

because the buyer might feel that excessive profits are generated in

the former case and that extreme caution during contract performance

is necessary in the latter case.

Matching the external and internal variables to these strategies

becomes the important step in determining buyer negotiation leverage

and flexibility. It is also important to understand that a change in

one variable is generally not an isolated event, but that it can

modify the parameters of most other variables leading to significant

shifts in the pricing approach. Certainly the buyer must have fairly

good knowledge of the seller’s costs, the earnings needed, and the

competitive nature of the company’s markets.

The buyer should aggressively and continually pursue data helpful to

assessing the external variables affecting pricing strategy.

Information concerning new versus mature products, product

differentiation, product life cycle, the competitive environment,

product demand, and industry capacity can all be obtained through

careful attention to various industry, trade association, financial,

and government publications. Factoring each of these external

variables into the process which favors one pricing approach over the

others allows the buyer to draw conclusions regarding the seller’s

proposed price.

Data on internal variables are more difficult to obtain and to assess.

Data may be nonexistent or expensive to acquire. Several of these

variables require the buyer to pay close attention to “signals”

provided by the seller during periods of buyer-seller interaction.

Such things as capacity levels, financial health, cost control,

capital structure, expected rates of return, internal accounting

methods, and estimating methods are all areas in which the seller may

be unwilling overtly to supply enough information for the buyer to

make legitimate assessments. The astute buyer must develop a feel for

each of these areas, particularly during the fact-finding portion of

negotiations and more generally during contract performance. In the

case of federal government contracts, data from many

of these areas must be provided as a condition of contract award.

Regardless of the difficulty involved, these variables are key to

understanding seller pricing behavior.

CONCLUSION

If the capability of a buyer is even slightly enhanced by an improved

ability to forecast a seller’s objectives, through an evaluation of

seller pricing strategy, then it seems clear that the use of this tool

is warranted. Many factors enter into the pricing decision, and there

are no simple formulas that can solve the pricing problem. A buyer may

not be able to investigate and examine each of these factors.

Nevertheless, a general awareness of their existence and their impact

will contribute significantly to preparation for contract

negotiations.

REFERENCES

1.

Stewart A. Washburn, “Estimating Strategy and Determining Costs in

the Pricing Decision,” Business Marketing, July 1985, p. 54.

2.

Willis R. Greer, Jr., “Early Detection of a Seller’s Pricing

Strategy,” Program Manager, November-December 1985, pp. 6-12.

3.

Joel Dean, “Pricing Pioneering Products,” Journal of Industrial

Economics, July 1969, pp. 165—79.

4.

Ibid., p. 167.

5.

F. M. Scherer, Industrial Pricing—Theory and Evidence (Berlin:

Rand McNally, 1970), p. 46.

6.

Gilbert Burck, “The Myths and Realities of Corporate Pricing,”

Fortune Magazine, April 1972, pp. 84-89.

7.

Wulif Plinke, “Cost-Based Pricing,” Journal of Business Research,

Vol. 13, 1985, pp. 447—60.

8.

Nancy S. Topic, “Fair and Reasonable Prices in Noncompetitive

Procurements. Unpublished research paper, Florida Institute of

Technology at Army Logistics Management Center, Fort Lee,

Virginia, June 1985, p. 6.

9.

ibid., p. 6.

10.

Frederic S. Lee, “The Marginalist Controversy and the Demise of

Full Cost Pricing,” Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. XVIII, No. 4

(December 1984), pp. 1107—32.

11.

Alfred R. Oxenfeldt, “A Decision-Making Structure for Pricing Decisions,”

The Journal of Marketing, January 1973, pp. 46-53.

12.

Thomas Nagel, “Economic Foundations for Pricing,” The Journal of

Business, Vol. 57, No. 1, Part 2 (January 1984), pp. 13-38.

13.

A.J. Burkart, “Pricing Policy,” Journal of Industrial Economics,

July 1969, pp. 180—87.

14.

Nagel, “Economic Foundations,” p. 29.

15.

Washburn, “Estimating Strategy and Determining Costs,” p. 64.

16.

Stanley N. Sherman, Government Procurement Management

(Gaithersburg, MD: Wordcrafters Press, 1985), p. 6.

17.

Douglas Moses and Shu S. Liao, “Predicting Bankruptcy of Private

Firms: A Simplified Approach,” Naval Postgraduate School Working

Paper No. 86- 18, July 1986.

18.

Greer, “Early Detection,” p. 10.

CHECKLIST FOR SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION BY EXAMINATION

CHECKLIST FOR SUBMISSION OF APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION BY EXAMINATION F EDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON DC 20554 FEBRUARY 11

F EDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON DC 20554 FEBRUARY 11 C IENCIA Y AMBIENTE – CUARTO DE PRIMARIA EL

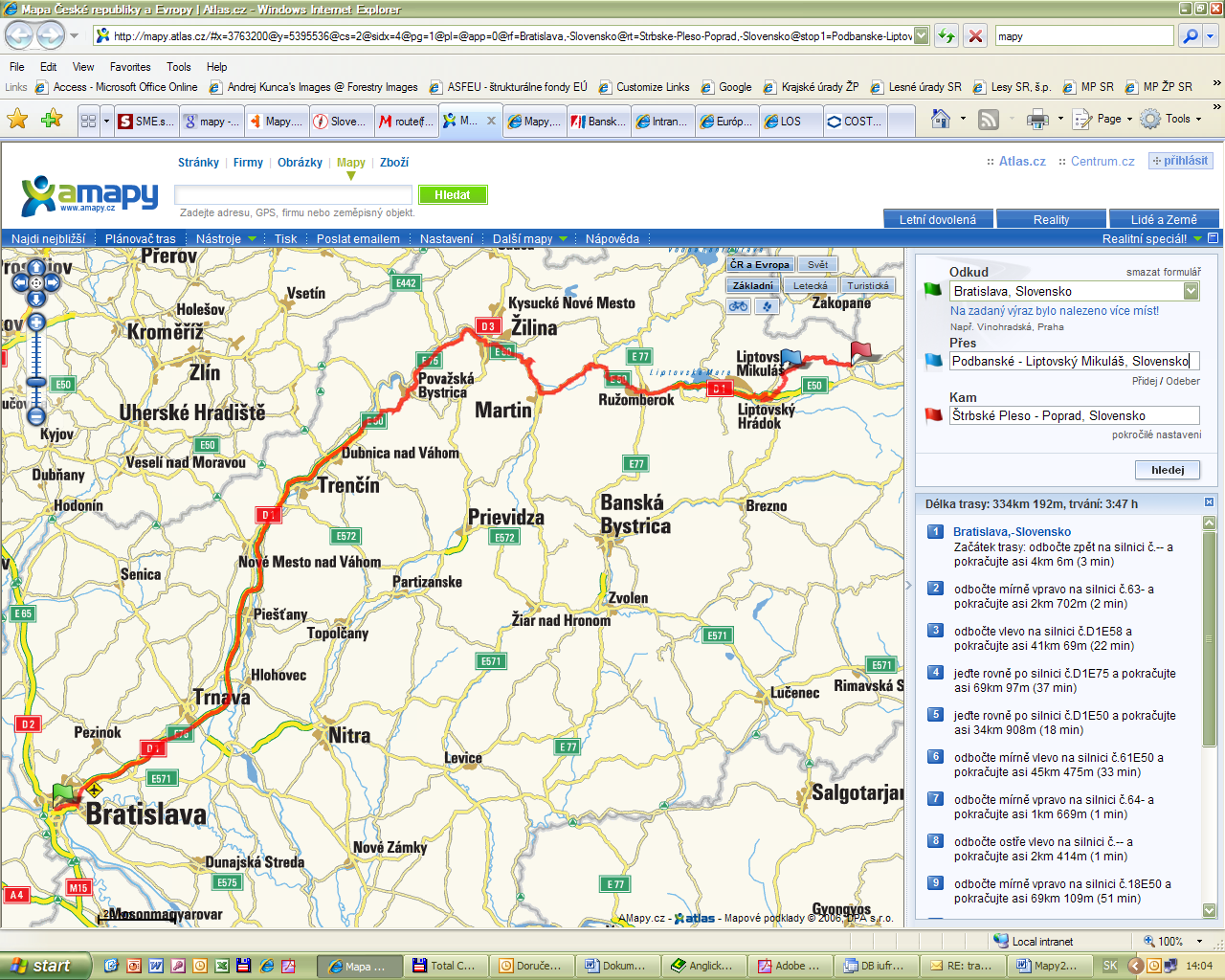

C IENCIA Y AMBIENTE – CUARTO DE PRIMARIA EL MAPS OF APPROACHING ROADS BRATISLAVA – ŠTRBSKÉ PLESO (N49°6´25´´

MAPS OF APPROACHING ROADS BRATISLAVA – ŠTRBSKÉ PLESO (N49°6´25´´ TRGOVINSKO UGOSTITELJSKA ŠKOLA TOZA DRAGOVIĆ’’ KREDITNA KARTICA I

TRGOVINSKO UGOSTITELJSKA ŠKOLA TOZA DRAGOVIĆ’’ KREDITNA KARTICA I JANUSZ SZYMBORSKI MA∏GORZATA LEWANDOWSKA WITOLD ZATOƑSKI NINA OGIƑSKABULIK TAMARA

JANUSZ SZYMBORSKI MA∏GORZATA LEWANDOWSKA WITOLD ZATOƑSKI NINA OGIƑSKABULIK TAMARA REGIÓN DE MURCIA AUTORIZACIÓN DE LOS PADRES PARA LA

REGIÓN DE MURCIA AUTORIZACIÓN DE LOS PADRES PARA LA