revised july 23, 2008 nepal i. does national or sub-national law or policy recognize terrestrial, riparian or marine ind

Revised July 23, 2008

Nepal

I.

Does national or sub-national law or policy recognize terrestrial,

riparian or marine Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas

(ICCAs)?

The government of Nepal does not legally recognize “indigenous and

community conserved areas” as a designation of terrestrial or riparian

management or as part of the national protected area system. Yet Nepal

is rich in ICCAs, including many customary ICCAs maintained by its

many Indigenous peoples and other local communities. Sacred natural

sites continue to be cared for and protected by many Indigenous

peoples and communities. Many communities also continue to manage

collective commons even though the lands themselves have been

nationalized over the past half century and customary law and

community regulatory practices are no longer legally recognized. Lack

of state recognition and support for these customary institutions and

practices contrasts with the devolution of some natural resource

management authority since the early 1990s to new, nationally-standard

local institutions designed and promoted by the central government and

transnational NGOs in conservation areas1, buffer zones, and the

national forest.2 These state (and NGO) initiated “community”

conservation institutions can be considered to be ICCAs in cases where

communities have full management authority over lands and waters and

manage them in ways that have conservation significance. Yet whether

or not such central government (or NGO) initiated and designed local

institutions should be considered to be ICCAs remains a much debated

issue in international and Nepal conservation circles and among

Indigenous peoples and other local communities. There remain questions

about whether nationally-implemented local institutions are truly

voluntarily adopted by indigenous peoples and local communities,

whether they are cases of community management or instead really

co-management arrangements, whether they embody international human

and indigenous rights standards (including those articulated in ILO

Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, which Nepal ratified

in 2007), and whether such new institutions and policies fully embody

indigenous and local communities’ conservation values, resource use

and conservation goals, culturally-based understandings about

appropriate means of decision-making and implementation, and

geographies of indigenous homelands and community lands.

Nepal’s protected areas – with the possible exception of Kangchenjunga

Conservation Area (see below) cannot be considered to be ICCAs.

Its nine national parks, three wildlife reserves, and its single

hunting reserve clearly are not ICCAs. They are administered by the

central government with no formal participation by communities. Two of

Nepal’s three conservation areas are co-managed by national NGOs and

the national government and also cannot be considered to be ICCAs. In

one case, Kangchenjunga Conservation Area (KCA), a regional NGO with

predominately indigenous membership now co-manages the protected areas

with the national government, and some Nepal government officials and

NGO staff consider that this constitutes an ICCA. They note that KCA

management authority was “handed over” in September 2006 to a 12

member Conservation Area Management Council composed of 9 elected

indigenous representatives (one each from seven regional, VDC (county

or sub-county) level, User Committees and two members of

settlement-scale “Mothers Groups”), a representative from the district

development committee, a social worker, and a “warden” or

superintendent appointed by the Department of National Parks and

Wildlife Conservation and further observe that following a March 2008

amendment to the KCA regulations the warden now has little role in the

management of the KCA). Skeptics caution that the KCA governance

structure constitutes a co-management arrangement in which indigenous

peoples have a strong role and note that it remains to be seen whether

the government will in effect adopt a purely advisory role such that

the KCA becomes a de facto ICCA.

Within all the conservation areas “Conservation Area Management

Committees” (CAMC; referred to as Conservation Area User Committees,

CAUC, in KCA), a new local institution created by the national

government, have considerable conservation management authority within

multi-village, United States county-sized “Village Development

Committees (VDCs),” and can delegate management to village-scale

sub-committees and user groups. These CAMCs/CAUCs must abide by

national conservation area policies (for example the national ban on

hunting in protected areas) but are otherwise empowered with

considerable authority to devise and implement local conservation

policies.

In the case of the buffer zones, which have been established adjacent

to national parks and wildlife reserves (and which can include

settlement enclaves within national parks), three different scales of

local and community conservation management institutions have been

established. These are a Buffer Zone Management Council with one local

representative from each Buffer Zone Users Committee, one Buffer Zone

Users Committee for each VDC or other area defined by the national

park or wildlife reserve superintendent, and one or more Buffer Zone

Users Groups at the local VDC ward scale (wards vary in size from

neighborhoods of large villages to micro-regions which include

multiple settlements). Community Forests User Groups (CFUGs) have been

established in the national forest at settlement and multi-settlement

VDC scales. As discussed in section III, buffer zone and national

forest institutions are new, standardized national institutions

designed by central government agencies which do not necessarily

acknowledge earlier community and indigenous peoples’ institutions,

policies, and practices. They are based on new local administrative

geographies which often ignore customary village land boundaries and

management of commons and instead group multiple villages into new

administrative units. Buffer zone establishment has also in some cases

provided national park and wildlife reserve administrators with

considerable policy-making, institutional oversight, and budget

allocation authority within the buffer zone. Indigenous peoples in

many buffer zones have objected that buffer zone administration has

extended the role of government protected area administrators into

their community lands and affairs and created what often constitutes a

weak co-management arrangement in which central government officials

dominate decision-making. Also of concern is the common situation in

the lowland buffer zones in which indigenous peoples – including

communities coercively displaced from national parks and wildlife

reserves – constitute only a small minority in a buffer zone where

non-indigenous local elites capture control of local participation in

governance and buffer zone benefits.

Pre-existing “customary” ICCAs (many of which continue in operation),

such as community management of sacred places and collectively used

forests and grasslands, have not been recognized in law or policy. The

category of “religious forests,” which is a legally authorized form of

devolving management authority over forests in the national forest and

in buffer zones, offers a potential means to recognize customary

sacred forests. Customary sacred forests, however, have seldom been

recognized as religious forests within national forests or in buffer

zones. No figures are available on the number or area of religious

forests, in contrast to readily available figures on the number of

community forest users groups and the areas they administer. It

appears there are few.

II.

Does the country recognize ICCAs as a part of the PA network

system?

Nepal does not recognize ICCAs as such as part of the national

protected area system. However, the Nepal protected area system

currently includes conservation areas and buffer zones, both of which,

as previously described, have within them one or more scales of local

administrative institutions (the Conservation Area Management Council

and Conservation Area Management Committees/User Committees in

conservation areas and Buffer Zone Users Councils, Committees, and

Groups in buffer zones). These may be considered non-traditional

ICCAs. In the case of conservation areas, CAMCs/CAUCs and CAUGs have

in the past functioned as ICCAs within protected areas which are

co-managed at the scale of the protected area as a whole by the

national government and a national NGO (the National Trust for Nature

Conservation – formerly the King Mahendra Trust for Nature

Conservation) and also formerly by World Wildlife Fund-Nepal.

The goals, institutional arrangements, and practices of pre-existing,

often still extant ICCAs including sacred places and community-managed

forests, grasslands, and alpine commons, can be legally incorporated

within these local and regional ICCA institutions. However,

pre-existing customary institutions and law are not inherently

recognized within conservation areas or in the rest of the Nepal

protected area system. Conservation Area Management Committees/User

Committees in conservation areas, Buffer Zone Users Committees and

User Groups, and Community Forest Users Groups, may in some cases

incorporate customary ICCA management goals and regulations into their

working plans and rules. There is no guarantee of this, however, and

customary ICCAs may often be ignored when indigenous peoples are

marginalized within multi-ethnic “local” scale “community” management

institutions. Traditional institutional structures and management

practices for indigenous and local community customary ICCAs may often

be undermined and lost. The extent to which this has happened or is a

current risk has not been documented.

Community forests users groups in the national forest are not

recognized as part of the PA network system because in Nepal the

national forest is not regarded as part of the PA network system. The

government of Nepal, unlike some other states, has not reported the

national forest to IUCN’s World Commission on Protected Areas (WCPA)

or the World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA) for recognition and

inclusion in the UN List of Protected Areas and the World Data Base on

Protected Areas.

III. If ICCAs are not legally recognized, are there general

policies/laws that recognize indigenous/community territories or

rights to areas or natural resources, under which such communities can

conserve their own sites?

The Nepal government first recognized indigenous peoples as such

(officially adivasi/janajati) by executive order in 1997 and by

national law in 2002. Currently, 59 such peoples have been identified

by the Nepal government. In 2007 the government of Nepal ratified ILO

Convention No. 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, becoming the

first country in mainland Asia to do so, and also voted in the UN

General Assembly to adopt the UN Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples. In early 2008 the government of Nepal agreed to

create autonomous states based on ethnicity in at least some parts of

Nepal, but what the federal map of Nepal will look like, which

indigenous peoples will have autonomous states, and what governance

authority will be delegated to them is not yet decided.

Collective ownership of forests or rangelands by communities is not

recognized in Nepal law. Prior agreements and promises to indigenous

peoples recognizing communal lands (kipat) have not been kept and

these were nationalized beginning in the 1960s. Large areas of such

collective lands have been incorporated in protected areas and the

national forest. Indigenous peoples and other local communities do not

have defined legal rights to the use of natural resources in the areas

in which they reside, but some uses can be authorized by protected

area administrators in some of the national parks and in buffer zones,

as well as in the community forests within the national forest.

The National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act of 1973 bans many

customary natural resource activities including hunting and grazing.

Very limited natural resource use (such as grass harvesting) is

permitted in some national parks on a fee basis and subject to limited

seasons and quantities. Protests by indigenous peoples have resulted

in some increased access to natural resources in several lowland

national parks and wildlife reserves in recent years, but these

concessions are not considered rights and in some cases have not been

maintained for long. There is no recognition of an inherent right to

use plants and animals in traditional religious activities.

People who live in and around mountain national parks (but not lowland

protected areas), however, are accorded conditional access to

subsistence use of natural resources by the Himalayan National Parks

Regulations of 1979. In several mountain national parks this has

included grazing and collection of deadwood for firewood. Customary

use of natural resources or customary levels of natural resource use

are not, however, rights. The regulations do not specify authorized

natural resource use and the conditions of use in any detail. Within

mountain national parks, management policies have tended to restrict

the range of land uses permitted and often also the level of use of

those permitted uses. Some customary uses – such as felling trees for

timber and for firewood -- have been banned or severely limited in

Himalayan protected areas (including both national parks and

conservation areas).

Protected area laws, policies, regulations, and plans often have been

developed with little participation by indigenous peoples and have

been adopted and implemented without their consent. No formal

participation in protected area management is recognized in any of the

protected areas other than Kangchenjunga Conservation Area. A Sherpa

national park advisory committee established in Sagarmatha (Mt.

Everest) National Park (SNP) in the 1970s was dissolved within a

decade. The current national park management plan calls for this to be

re-established and such an advisory committee may be included in SNP

Regulations which are now under development.

Land Nationalization and community conserved areas

In Nepal almost all forest, all grasslands, and other non-cropped land

such as the alpine areas, lakes, and rivers have been nationalized

under the Private Forests (Birta) Nationalization Act of 1957 (which

has been interpreted to include community owned and managed forests as

private forests subject to nationalization) and the Rangelands

(Pasture Lands) Nationalization Act, 1974. There has been no

subsequent restitution of forest or grasslands to community ownership.

All of the nationalized forest was formerly managed by the Department

of Forests (DoF), and the DoF retains direct or supervisory authority

over the management of the national forest (including shrubland,

grassland, wetland, lacustrine, riverine, and alpine areas within).

Administrative authority over what is now the land in the national

parks, wildlife refuges, conservation areas, hunting reserve, and

buffer zones has been transferred to the Department of National Parks

and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), another department within the

Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation. Another approximately 25%

of the national forest has now been handed over to community

management under DoF supervision as “community forests.” DNPWC is

responsible for administrative oversight of protected areas, including

buffer zones. Neither the DNPWC nor the DoF recognizes any inherent

rights by communities to continue to manage lands according to

customary or traditional institutions and practices. Land management

by customary or traditional institutions, however, continues and in

some cases, as in Sherpa community management of grazing on national

park rangelands, has been tacitly recognized by DNPWC. Since the early

1990s, various new forms of “user committee” or “user group” based

management have been established in buffer zones, conservation areas,

and some national forest areas. These are not based on customary or

traditional institutions or administrative areas. Their policies may

or may not reflect customary practices.

National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, Conservation Areas

With the third amendment to the National Parks and Wildlife

Conservation Act in 1989 the DNPWC began to co-manage conservation

areas with NGOs. Until 2006 these NGOs were either the National Trust

for Nature Conservation (formerly the King Mahendra Trust for Nature

Conservation) or the World Wildlife Fund. In September 2006, however,

the national government and WWF-Nepal announced the "hand over" of

legal co-management and effective, de facto management of

Kangchenjunga Conservation Area to a local NGO, the Kangchenjunga

Conservation Area Management Council (KCAMC), the first time that

indigenous peoples have gained co-management or management authority

over a Nepal national government-recognized protected area. Legal

transfer of greater management authority to the Indigenous members of

the KCAMC, however, required an amendment to the DNPWC KCA

Regulations. This was belatedly signed by the Minister of Forests and

Soil Conservation only in March 2008. Local conservation management

within conservation areas is largely carried out by local

institutions. Under conservation area guidelines developed by the

DNPWC in 1999, local administrative bodies known as “Conservation Area

Management Committees” (and called Conservation Area User Committees

in Kangchenjunga Conservation Area) are created and manage forests and

other lands. These are not customary community institutions that

manage village lands. Instead these institutions each administer all

or part of the territory of a so-called “Village Development Committee

(VDC),” a local administrative unit introduced by the Nepal national

government in 1990 which typically combines the customary village

lands of several (and sometimes scores) of settlements. The new

Conservation Area Management Committees/User Committees manage

forests, grasslands, and other lands under the supervision of NGOs and

DNPWC and within national laws. They do not necessarily respect the

customary regulations through which individual settlements formerly

managed forests, grasslands, and sacred places, and there are no

regulations or guidelines requiring or advising them to do so. In

Annapurna Conservation Area, however, Conservation Area Management

Committees in at least some regions have adopted regulations and

practices which recognize customary ICCAs.

National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act, Buffer Zones:

Under the authority of the fourth amendment to the National Parks and

Wildlife Conservation Act in 1993 the DNPWC has similarly handed over

management authority over lands that include forests, grasslands, and

alpine regions to several new local administrative bodies established

within buffer zones at varying scales (Buffer Zone User Groups at the

ward or settlement level, Buffer Zone User Committees at the VDC level

(or sub-VDC or multiple VDC level as authorized by protected area

superintendents), and a Buffer Zone Management Committee for the

entire buffer zone). The Buffer Zone Management Committee, composed of

the chairs of each of the Buffer Zone User Committees), the

superintendent (chief conservation officer or warden) of the national

park or wildlife reserve, and a district official, co-manages

conservation in the buffer zone. In some cases effective authority may

reside with the superintendent and the BZMC may become in effect an

advisory body. Local administrative units (Buffer Zone Users Groups

and Buffer Zone User Committees) manage forests and grasslands within

the buffer zone. One (or more) Buffer Zone Users Groups administers

one or more of the nine wards within each VDC. Because each ward

typically contains multiple settlements, the use of this new

administrative geography ensures that sacred places and community

managed commons that were formerly administered by particular

individual villages now come under the management of committees that

include members from villages which formerly did not have access

rights to them and who were not involved in the past in their

management. The various buffer zone institutions manage or co-manage

only buffer zone lands, and have no official role in the management of

adjacent national parks or wildlife reserves. In the case of

Sagarmatha National Park, however, the Buffer Zone User Committees and

the Buffer Zone Management Committee have been integrally involved

since 2002 in developing and administering new forest use rules for

the national park forests.

Community-based Management within the National Forest

The Department of Forests has similarly “handed over” management

authority over forests (and shrublands and grasslands) within the

national forest to new local institutions (Community Forest Users

Groups), which can be organized at the hamlet (ward), settlement, or

multi-settlement scale. These institutions manage forests and other

areas under the supervision of district forest offices after adopting

a Department of Forests-approved constitution and five-year

operational plan. This institution enables communities to regain some

degree of authority and control over managing local forests and an

opportunity to adopt new forest management goals and procedures,

including permit and fee systems and regional working plans intended

to maintain sustainable use and provide community and government

revenue. The opportunity to regain a measure of control over and

benefit from local forests may be welcomed by communities, although

the new institutions, procedures, policies, and conservation goals can

be controversial within communities when new conceptions of

conservation, new decision-making processes, and new resource use

allocation, restrictions, and procedures conflict with customary

values, institutions, and practices and when they are considered to

unequally benefit and disadvantage particular individuals and social

groups within what are often politically, socially, ethnically, and

economically differentiated communities.

Community-based Management in National Parks

The Sherpa declaration of all of Sagarmatha National Park and Buffer

Zone as an ICCA, the Khumbu Community Conserved Area (KCCA), is an

invitation to the DNPWC and the Nepal government to respect,

coordinate with, and legally recognize ICCAs. The KCCA encompasses a

1,500 km2 region which Sherpas consider to be a beyul, a sacred,

hidden valley and a Sherpa homeland. The region has many sacred

mountains and other natural sites, including temple forests and

“lama’s” forests which Sherpas strictly protect from any tree-felling

through local ICCAs. Sherpas protect all wildlife within the region,

which as a result has significant populations of endangered and rare

wildlife including snow leopards, musk deer, red panda, and Himalayan

tahr. Sherpa communities, buffer zone institutions, and NGOs also

maintain a number of local/regional customary and new ICCAs which

manage Sherpa livelihood use of forests, alpine areas, and grasslands

within the area of the KCCA.

Although there is not yet a legal basis to recognize the KCCA in SNP

planning and policies as such, Sherpa conservation values and

stewardship of the region, its sacred status for them, and their local

and regional ICCAs could be acknowledged and respect for them could be

coordinated in SNP management plans, policies, and practices. While

future management plans and regulations will be able to be framed with

awareness of and appreciation of the KCCA, the present 2006-2011

Sagarmatha National Park and Buffer Zone Management Plan, which was

devised before the KCCA was declared, proposes the establishment of

national park zoning in a way that could readily be based on Sherpa

ICCAs. The management plan envisions zoning the national park into two

types of zones: “community resource areas” and “special areas.” Buffer

zone residents residing in the enclave settlements within the national

park would have access to some natural resources within these national

park zones (particularly in community resource areas) and may be

involved in the management of forest use, grazing, and other land use

in them. Details of these arrangements, including whether and how

communities participate in management of land use in the new zones,

have yet to be worked out. Zone boundaries also require further

discussion as the “special areas” include much of the forest which

Sherpas rely on for firewood. Sherpa leaders hope that zoning

boundaries will be based on Sherpa land use and management maps which

they are now involved in preparing and which will provide the first

detailed maps of the geography of community and regional ICCAs.

“Special zones” could be used to honor and protect Sherpa sacred

places such as temple and lama’s forest ICCAs. The “community resource

areas” could be demarcated along the lines of existing community use,

and it could be specified that their management continues according to

existing community/buffer zone ICCAs.

Overall Policy

Strengths :

1. Since the late 1980s, the national government of Nepal has

recognized several forms of community-based conservation within its

protected area system and has "handed over" considerable management

authority to local institutions in conservation areas and in buffer

zones in and around national parks and wildlife reserves. Management

authority of a substantial part of the national forest has also been

"handed over" to communities.

2. The current institutions have transferred some degree of

decision-making and management from the central government to

communities in conservation areas, buffer zones, and community forests

within the national forest. They have also increased access by

indigenous peoples and local communities to natural resources (except

within lowland national parks and wildlife refuges). Despite

decentralization, however, the degree to which communities have

authority over policy-making and planning varies. In particular,

communities have been little involved in national park or wildlife

reserve management.

3. Since 1992, three conservation areas have been established,

encompassing 9,827 km2. These constitute three of the four largest

protected areas in Nepal. Annapurna Conservation Area (7,629 km2),

Nepal’s largest protected area, is more than twice the size of any

other protected area in the country and is home to more than 100,000

people living in more than 300 villages. Since 1996, eleven protected

area buffer zones have been established in association with national

parks and wildlife reserves, constituting nearly 5,000 square

kilometers of the 28,999 square kilometer protected area system that

now encompasses 19.7% of Nepal (including buffer zones but not

including the national forest). As of 2005, 153 buffer zone community

forestry user groups had been established. The eight buffer zones

established adjacent to national parks have an area of 4,365 km2 and

encompass 144 VDCs. In 2006 they were inhabited and managed by an

estimated 70,000 households (447,000 people). Approximately 25% of the

national forests, an area of 1.2 million hectares, had been handed

over by 2005 to more than 14,000 community forest management

committees. Some 1.6 million households (7.7 million people), more

than 25% of the population of Nepal, are involved in managing

community forests.

Weaknesses:

There are a number of continuing weaknesses in the current level of

recognition of ICCAs within protected areas and the national forest.

Customary ICCAs have little legal recognition within or outside of

existing protected areas. Indigenous rights recognition is not

integral to protected area governance and management and this is

evident in the lack of legal recognition of indigenous peoples’

territories, collectively-owned land, or customary collective

management of commons and sacred places; the lack of acknowledgement

that indigenous peoples and other local communities have spiritual

relationships with territory, sacred places, and non-human species

which are of conservation importance; and the lack of recognition that

indigenous peoples have rights to customary use and management of

biological resources in accordance with traditional cultural practices

and conservation goals. The Nepal protected area system continues to

be based primarily on state governance of protected areas, with

co-management only of conservation areas and buffer zones, rather than

embodying a diversity of governance approaches as advocated by IUCN

and by the Programme of Work on Protected Areas of the Parties to the

Convention on Biological Diversity.

1. The government of Nepal has legally recognized 59 indigenous

peoples and it ratified ILO Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal

Peoples in August 2007, but has not yet legally recognized many of the

indigenous rights specified in it.

2. Nepal’s protected areas (including buffer zones) were established

by government decrees without prior, free, informed consent by

resident indigenous peoples and other local communities. Although

indigenous peoples and other local communities were sometimes

consulted in the process of protected area establishment and

development through the convening of village meetings, this did not

constitute prior consent. In some cases protected areas were

established even though Indigenous peoples indicated they were opposed

to them.

3. Indigenous peoples and other local communities have been physically

displaced from several of Nepal’s national parks and wildlife reserves

. Indigenous peoples reportedly have been involuntarily evicted from

Rara National Park, Chitwan National Park, Bardia National Park, Kosi

Tappu Wildlife Refuge, Suklaphanta Wildlife Reserve, and Parsa

Wildlife Reserve.

4. Indigenous peoples and other local communities have been

"economically displaced" from all of Nepal’s national parks, wildlife

reserves, conservation areas, and hunting reserves, from many of its

buffer zones, and from many areas of its national forest because of

national government imposed bans or restrictions on their customary

access to natural resources (including the use of natural resources

for religious practices). Indigenous peoples often were not consulted

on the implementation of these policies and did not give their free,

informed, prior consent to them. Protected area policies have also

politically, socially, and culturally displaced indigenous peoples and

local communities through undermining their customary laws,

institutions, and practices and ignoring indigenous rights.

5. Indigenous peoples and other local communities were little involved

in decision-making about land management and conservation in protected

areas prior to the 1990s, and since then their involvement has been

limited to conservation areas, buffer zones, and community forests

within the national forest. They remain little involved in the

management of the national parks or the wildlife refuges.

6. The government of Nepal does not recognize indigenous territories,

community territories, or community ownership of land. Nearly all

forests and grasslands have been nationalized in the past half-century

and none has been restored to community ownership.

7. Customary systems of collective management of land, including

forest and rangeland commons, are not recognized in protected areas or

the national forest. New, nationally developed local institutions

introduced in buffer zones, conservation areas, and community forests

often do not incorporate customary community practices of managing

natural resource use or protecting sacred places.

8. Many customary uses (economic and cultural) of biological resources

by indigenous peoples are not fully recognized in protected areas.

Typically some activities are banned while others may be restricted in

season and in level of use.

9. Local administrative units of land management in protected areas

and community forests have been devised and territorially delineated

by the national government and often do not reflect customary or

traditional patterns of community land ownership and administration.

This can undermine customary, settlement-based management of commons

and protection of sacred places by ignoring communities’ customary or

traditional governance institutions, conservation goals, and land use

regulations.

10. Little use has been made thus far of the designation of “religious

forests” in buffer zones or the national forest. This misses an

opportunity to acknowledge pre-existing community conserved areas.

11. There is no national legal basis for the identification and

protection of sacred places or for assurance that indigenous peoples

will continue to have access to and control over their management.

There are likely thousands of sacred forests, mountains, lakes, and

other community conserved areas within the regions inhabited by

indigenous peoples and other local communities. Communities have lost

their ownership of these with land nationalization. Villages often no

longer have control over decisions about the protection of their

sacred sites because new land management institutions in conservation

areas, buffer zones, and community forests are based on regional,

multi-village governance rather than on governance by individual

villages.

12. Until very recently, when co-management authority over

Kangchenjunga Conservation Area was handed over to a local NGO,

indigenous peoples did not manage or co-manage any of Nepal’s

protected areas. The government of Nepal does not recognize any

inherent right for indigenous peoples to be involved in the management

of national parks and wildlife reserves. Following a national

government policy initiative in 2003, however, management or

co-management of some (but not all) national parks, conservation

areas, and wildlife refuges can be "handed over" to NGOs, including

local NGOs. Such NGOs, even when locally created, however, may not

constitute elected, representational governance and may not

incorporate or recognize indigenous peoples' customary governance

institutions and natural resource management practices.

IV.

Overall Comments

1. Nepal has a worldwide reputation for progressive, community-based

conservation in its conservation areas, buffer zones, and national

forest. Nepal has -- in effect, if not by name -- recognized

newly-established community conserved areas within these protected

areas and areas of the national forest. These are, however, recent

institutions established through state devolution of some natural

resource management authority in particular sites. Nepal has yet to

adopt policies which recognize and support “customary” or

“traditional” ICCAs such as sacred places and community-managed

commons in either its current protected area system or its

nationalized forests.

2. A comprehensive recognition of customary ICCAs in Nepal would have

enormous indigenous rights and conservation significance. Indigenous

peoples constitute at least 38% of the country’s population. Most of

these more than eleven million people continue to live in rural areas,

many of them in customary homelands. They and other local communities

historically have respected and conserved a vast number of

collectively-managed forest and grassland commons and sacred places. A

large number of these systems may still be in use despite lack of

legal recognition, and indigenous peoples and local communities may

wish to revive others.

3. Formal recognition of ICCAs throughout the Nepal protected areas

and the national forest would likely require amendments to several

government acts, including the National Parks Act (or a new Protected

Areas Act), the Himalayan National Parks Regulations (and individual

protected area acts), and the Forests Act. Guidelines, regulations,

and rules devised by the DNPWC for national park buffer zones and

conservation areas, and by the DoF for community managed forests,

should also be evaluated and revised to recognize ICCAs and to come

into accord with current IUCN and CBD guidelines for protected area

establishment and management in regions inhabited by indigenous

peoples and local communities.

4. It would be appropriate for the government of Nepal to consider

evaluating the suitability of its national forest for inclusion on the

UN List of Protected Areas. Large areas of the national forest could

be classified as IUCN Category V or VI protected areas, including

areas managed by Community Forest Users Groups

5. Linking national recognition of ICCAs within Nepal’s protected

areas and national forests with enhanced indigenous rights recognition

is also advisable. Although Nepal is often commended for its

recognition of community-based conservation in its protected area

system and its community forestry programs, from the standpoint of

ICCAs and the recognition of the rights of indigenous peoples within

and around protected areas these vary enormously in how well they meet

international standards adopted by IUCN for the establishment and

management of protected areas in regions inhabited by indigenous

peoples. There are important shortcomings with regard to

acknowledgement of the rights of indigenous peoples and customary

community-based conservation even in the most progressive protected

areas in Nepal (the three conservation areas and the buffer zones) and

the Community Forest User Group-managed areas of the national forest.

These shortcomings are more pronounced in the national parks and

wildlife reserves. Key concerns are recognition of collective

territorial governance and collective land ownership, restitution of

lands which have been nationalized, informed consent by indigenous

peoples to the establishment and operation of protected areas, access

to customarily used natural resources for economic and cultural

purposes, community care and protection of sacred places, and the

rights of communities to manage natural resources and participate in

conservation and development on the basis of their own systems of

governance and their knowledge, values, beliefs and practices.

Prepared by:

Dr. Stan Stevens, Associate Professor of Geography, Department of

Geosciences,

University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA 01003, USA.

Email: [email protected]

1 “Conservation Area” is a type of protected area authorized by Nepal

national government legislation which is dedicated to conservation and

“balanced utilization “ of natural resources. Conservation areas are

co-managed by the state and NGOs or communities and do not have

rangers, game scouts, and an army “protection unit” typical in the

country’s national parks and wildlife reserves.

2 Nepal has designated most of its forests as its “national forest”

under the management of the district forest offices (DFO) and the

supervision of the Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation. Some

areas of the national forest have been “handed over” to management by

“community forest users groups.” Unlike the practice in some

countries, the “national forest” has not been divided into multiple,

individually demarcated and named national forests.

19

TRANSSC2200510 PAGE 17 NATIONS UNIES E CONSEIL ÉCONOMIQUE

TRANSSC2200510 PAGE 17 NATIONS UNIES E CONSEIL ÉCONOMIQUE ZPRÁVA O ČINNOSTI VÚBP ZA ROK 2001 ORGANIZAČNÍ

ZPRÁVA O ČINNOSTI VÚBP ZA ROK 2001 ORGANIZAČNÍ 1 02009 12012 HJÄLP MIG DÅ JAG DÖR ATT

1 02009 12012 HJÄLP MIG DÅ JAG DÖR ATT Physics Challenge Question 16 Solutions Part 1 an Object

Physics Challenge Question 16 Solutions Part 1 an Object ANEXO I SOLICITUD DE SUBVENCIÓN PLAN DE EMERGENCIAS 2020

ANEXO I SOLICITUD DE SUBVENCIÓN PLAN DE EMERGENCIAS 2020 ZNAK SPRAWY172009 PRZEDSIĘBIORSTWO PRODUKCYJNO USŁUGOWO HANDLOWE „RADKOM” SP Z

ZNAK SPRAWY172009 PRZEDSIĘBIORSTWO PRODUKCYJNO USŁUGOWO HANDLOWE „RADKOM” SP Z COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO FICHA DE MATERIA DE

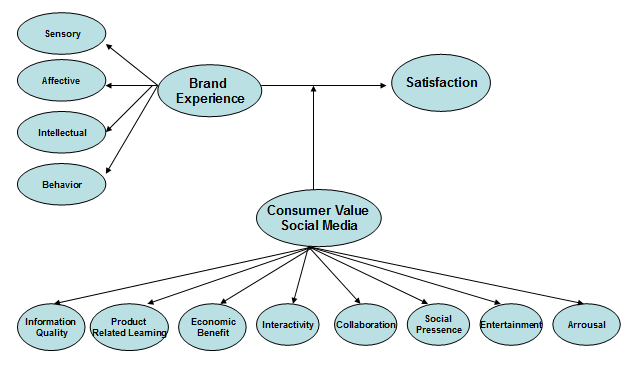

COMISIÓN DE ESTUDIOS DE POSGRADO FICHA DE MATERIA DE RESEARCH PROPOSAL A STUDY OF RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BRAND EXPERIENCE

RESEARCH PROPOSAL A STUDY OF RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BRAND EXPERIENCE (PHOTOGRAPH) STAFF APPLICATION FORM ACADEMIC YEAR FOR THE MOBILITY

(PHOTOGRAPH) STAFF APPLICATION FORM ACADEMIC YEAR FOR THE MOBILITY C ENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN DE LAS FOCES OFICINA DE

C ENTRO DE INTERPRETACIÓN DE LAS FOCES OFICINA DE KARTA USŁUG NR WKM13 WYDZIAŁ KOMUNIKACJI STAROSTWO POWIATOWE

KARTA USŁUG NR WKM13 WYDZIAŁ KOMUNIKACJI STAROSTWO POWIATOWE 3 LABORATORIO DE CIRCUITOS DIGITALES PRACTICA 7 CIRCUITOS

3 LABORATORIO DE CIRCUITOS DIGITALES PRACTICA 7 CIRCUITOS ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE DOCTORADO SOLICITUD DE ADMISIÓN A ESTUDIOS

ESTUDIOS OFICIALES DE DOCTORADO SOLICITUD DE ADMISIÓN A ESTUDIOS INFORME GLOBAL DE SERVICIO SOCIAL FECHA DE ENTREGA

INFORME GLOBAL DE SERVICIO SOCIAL FECHA DE ENTREGA