children’s experiences of disability – pointers to a social model of childhood disability word count for article and abstract – 7000 words

Children’s experiences of disability – pointers to a social model of

childhood disability

Word count for article and abstract – 7000 words

Introduction

Disabled children have received little attention within the social

model of disability: the extent to which it provides an adequate

explanatory framework for their experiences has been little explored.

Many studies about disabled children make reference to the social

model, often in relation to identifying social or material barriers or

in formulating recommendations for better services (Morris 1998a,

Dowling and Dolan 2001, Murray 2002, Townsley et al 2004, Rabiee et al

2005). Few have focused specifically on children’s perceptions and

experiences of impairment and disability, or explored the implications

of these for theorizing childhood disability. Watson et al (2000), and

Kelly (2005) following Connors and Stalker (2003a), are notable

exceptions. Ali et al (2001), in a critical review of the literature

relating to Black disabled children, conclude that the disability

movement in Britain has neglected children’s experiences.

The research reported in this paper was a two-year study conducted in

the Social Work Research Centre at the University of Stirling, funded

by the Scottish Executive. A full account can be found in Connors and

Stalker (2003b). The paper begins by outlining the study’s theoretical

framework, which drew on insights from disability studies and the

sociology of childhood. The study’s aims and methods are outlined and

some key findings presented. We conclude by speculating why most of

the children focused on ‘sameness’ rather than difference in their

accounts and the implications of the findings for developing a social

model of childhood disability.

Theoretical Framework

The Sociology of Childhood

Until the early 1990s, research on childhood was largely concerned

with children's psychological, physical and social development.

Children were usually prescribed a passive role in this process and

seen through adult eyes (Waksler 1991, Shakespeare and Watson 1998):

they were adults in training. The idea that childhood, unlike

biological immaturity, might be a social construction influenced by

factors such as class, gender and ethnicity emerged through the

'sociology of childhood'. Here, children are recognised as having a

unique perspective and actively shaping their own lives (James 1993,

James and Prout 1997, Mayall 2002). Listening to children's accounts

of their experiences has encouraged recognition that their lives are

not homogenous and need to be studied in all their diversity (Brannen

and O' Brien 1995). In order to understand general themes in

children's lives, it is necessary to pay attention to their narratives

and personal experiences. Shakespeare and Watson (1998) pointed to the

potential for drawing on insights from both the social model of

disability and the sociology of childhood to explore disabled

children’s experiences.

Reliance on personal experience, which constitutes much of research

with children, has been a contested area within disability studies.

Finkelstein (1996) questioned its relevance, believing that attempts

on the part of disabled people to describe the detail of their lives

is a route back to viewing disability as a tragic event which

‘happens’ to some individuals. Several disabled feminists (Morris

1993, Crow 1996, Thomas 1999) have suggested that not to do so is to

ignore lessons from the feminist movement:

In opposition to Finkelstein’s view that a focus on individual lives

and experiences fails to enable us to understand (and thus to

challenge) the socio-structural, I would agree with those who see life

history accounts…….as evidence that ‘the micro’ is constitutive of

‘the macro’. Experiential narratives offer a route to understanding

the ‘socio-structural’. (Thomas 1999, p78)

The social relational model of disability

Thomas’ work (1999) was particularly important to our study because

she has developed definitions of disability which relate directly to

people’s lived experience. She views disability as being rooted in an

unequal social relationship. It follows a similar course to racism and

sexism and results in 'the social imposition of restrictions of

activity on impaired people' by non-impaired people, either through ‘barriers

to doing’ or ‘barriers to being'. The former refers to physical,

economic and material barriers, such as inaccessible buildings or

transport, which restrict or prevent people from undertaking certain

activities; the latter refers to hurtful, hostile or inappropriate

behaviour which has a negative effect on an individual’s sense of

self, affecting what they feel they can be or become. Thomas calls

this process ‘psycho-emotional disablism’. Barriers to being are not

confined to the personal, one to one level: exclusionary institutional

policies and practices can have the same effect.

Thomas also identifies impairment effects, that is, restrictions of

activity which result from living with an impairment. This could

include the fatigue or discomfort associated with some conditions, or

the inability to do certain things. Historically, disability studies

has avoided acknowledging the limitations which can be associated with

impairment, (Crow 1996). Shakespeare and Watson (2002) see this as a

great weakness in social model theory, arguing that impairment is

'experientially .... salient to many'. Thomas (2001) suggests that

acknowledging personal experiences of living with impairment and

disability is politically unifying because it enables a full range of

disability experiences to be recognised and this inclusivity will

better represent all disabled people in society (Reeve 2002).

Difference

The idea of difference is another debate within disability studies

relevant to our research. One view is that difference does not exist

but rather individuals' bodies are constructed and then maintained as

disabled by social opinions and barriers (Price and Shildrick 1998).

An alternative view is that disabled people are 'essentially'

different from non-disabled people (Thomas 1999) so that difference is

part of the 'essence' of a disabled person. For Morris (1991), having

an impairment makes a person fundamentally different from someone who

does not have one. This difference exists beyond the socially

constructed effects of disablism, making the presence of impairment

the key difference between disabled and non-disabled people.

Scott-Hill (2004) suggests that difference has been neglected because

its acknowledgement poses a threat to the disabled people’s movement

and its political message: she calls for more ‘dialogue across

difference’.

The fusion of ideas from disability studies and the sociology of

childhood is at an early stage and while there are reasons to be

cautious, there are indications that it could be a very fruitful

relationship (Watson et al 2000) as we seek a framework within which

to understand and describe the richness and diversity of disabled

children's everyday lives.

Study aims and methods

The aims of the study were

*

To explore disabled children’s understandings of disability

*

To examine the ways in which they negotiate the experience of

disability in their daily lives

*

To examine the children’s perceptions of their relationships with

professionals and their views of service provision

*

To examine siblings’ perceptions of the effects on them of having

a disabled brother or sister,

In this paper, we focus on the first of these aims.

At the beginning of the study – when the research proposal was being

written – we recruited two ‘research advisors’, aged 11 and 12,

through a voluntary organization for disabled people. The children

gave us valuable advice about the design of information and consent

leaflets for different age groups, the wording of questions and the

suitability of interview materials.

Families were recruited to the study through schools and voluntary

organizations, which were asked to pass on letters to parents, and

information leaflets and ‘agreement forms’ to children. We were not

aiming to recruit a representative sample but rather to include

children and young people from a range of age groups, with a variety

of impairments, attending different types of school, and so on. Twenty

five families, who had 26 disabled children in total, agreed to take

part.

Before formal data collection commenced, an initial visit was made to

each family to discuss the implications of participating in the

research. This provided an opportunity for researcher and family

members to begin to get to know one another, agree ground rules,

ensure that everyone understood what the study entailed and had an

opportunity to ask questions or raise concerns. This meeting enabled

the researchers to identify each child’s accustomed communication

method and to some extent assess their cognitive ability, thus

enabling us to use an appropriate approach in the interviews.

One-to-one guided conversations were conducted with the young disabled

people in their own homes, spread over two or three visits. With

younger children, a semi structured interview schedule was used,

supplemented by a range of activities and communications aids, such as

‘spidergrams’, word choice exercises and picture cards, to engage the

child’s interests and facilitate communication. This approach was also

used with all the youngsters who had learning disabilities: piloting

showed that the more structured format of this questionnaire was more

accessible to this group than the topic guide (covering the same

subjects) designed for older children.

We asked the children to tell us about ‘a typical day’ at school and

at the weekend, relationships with family and friends, their local

neighbourhood, experiences at school, pastimes and interests, use of

services and future aspirations. While open-ended questions were

enough to launch some children on a blow-by-blow account of, for

example, everything they had done the previous day, other youngsters,

notably those with learning disabilities, needed the question broken

up into more manageable chunks, such as ‘what time do you usually get

up? What do you like for breakfast?’ We did not include direct

questions about impairment in the children’s interview schedules: nor

did we think it appropriate to ask the children, in so many words, how

they ‘understood disability’. Rather, we preferred to wait and see

what they had to say on these topics while telling us about their

daily lives generally and in response to specific questions like

*

‘Are there some things you are quite good at?’

*

‘Are there any things you find difficult to do?’

*

‘What’s the best thing about school?’

*

‘What’s the worst thing?’ ‘

*

Have you ever been bullied at school?’

*

‘Are there any things you need help to do?’ and

*

‘If you had a magic wand and you could wish for something to

happen, what would you wish?’

If individual children made little or no reference to impairment as

the interview proceeded, we raised the subject in follow-up questions,

eg: after the ‘magic wand’ question, we might ask ‘What about your

disability? Would you change anything about that?’ This was easier

with those who had physical or sensory impairments than those with

learning disabilities (see Stalker and Connors (2005) for an account

of these children’s views and experiences).

Over the last decade, an increasing number of publications have

offered guidance on seeking the views of disabled children for

consultation or research (eg: Ward 1997, Morris 1998b, Potter and

Whittaker 2001, Stone, 2001, Morris 2003). In our experience, talking

to disabled children is often no different from talking to any child:

it is important to see every child as a child first and with an

impairment, second. However, one of the authors (Connors), who

conducted most of the fieldwork, is fluent in British Sign Language

and Makaton: the ability to draw on these methods was essential to

avoid excluding four children from the study. A fifth child used

facilitated communication: his mother went through some of the

questions with him and passed on the responses to us. Two children had

profound multiple impairment and here we interviewed their parents,

although being careful not to treat their views as ‘proxy’ data.

Ethical issues are heightened in research with children. Consent was

treated as an on-going process: thus, we asked the children at the

start of each session if they felt okay about talking to us again,

checked that we could tape record what they said, reminded them they

could stop at any time or ‘pass’ on any question they did not wish to

answer and that nothing they said would be reported to their parents,

unless it indicated the children were at risk of harm. One child

decided not to proceed with a second interview – which (despite losing

potentially valuable data!) reassured us that he did not feel under

pressure to participate.

The children, 15 boys and 11 girls, were aged between 7 and 15. There

was one Black child, reflecting the relatively low population of Black

and minority ethnic families in Scotland, and all had English as their

first language. We deliberately avoided using medical diagnoses to

recruit children and did not ‘measure’ severity of impairment but

simply recorded any conditions or diagnoses which parents or schools

tgave us. Broadly, 13 children were described as having learning

disabilities, five, sensory impairments and six, physical impairments.

As noted above, two had profound/ multiple impairment. The youngsters

attended a variety of schools – ‘special’ (segregated), mainstream

(inclusive) and ‘integrated’ (segregated units within mainstream

schools). All lived in central or southern Scotland.

Twenty-four siblings and 38 parents also took part in one interview

each. Semi structured schedules were used to explore their views and

experiences – but these are not reported in detail here (see Stalker

and Connors (2004) re. siblings’ views about impairment, disablism and

difference).

Data recorded on audio or video tape (interviews conducted in British

Sign Language) were transcribed in full. The transcripts were read

through carefully several times, a sample being read and discussed by

both authors. Emerging patterns, common themes and key points were

identified and these, together with additional material taken from

field notes and pen profiles of the families, were used to distil the

findings.

Full details of the methodology can be found in Stalker and Connors

(2003).

Findings

The findings suggest that children experienced disability in four

ways, in terms of impairment, difference, other people's reactions and

material barriers.

Impairment

Much of what children talked about as ‘disability' was impairment and

the effects of impairment on their day to day living. (None used the

word 'impairment'). Children's main source of information about the

cause of their impairments was their parents. Parents told us they

tended to use one of three explanations: the child was 'special',

impairment was part of God's plan for the family, or there had been an

accident or illness around the time of birth. Several parents

commented on their dread at being asked for explanations and it was

notable that disabled children seemed to ask once and then let the

subject drop; perhaps they were aware of the distress felt by parents.

Generally, there seemed not to be much discussion within families

about impairment. A number of children had never talked to their

parents about it and, in some families, there was avoidance and/or

silence about the subject. One sibling, a 13 year old boy, reported

that his mother had forbidden him to tell other people about his

sister’s impairment but rather to ‘keep it in between the family’.

The disabled children tended to see impairment in medical terms - not

surprisingly, given that most had a high level of contact with health

services. Most had experienced multiple hospital admissions,

operations and regular outpatient appointments - all of which might

lead them to conclude that having an impairment linked them directly

to healthcare professionals. A few had cheerful memories of being in

hospital; for example, one said she would give her doctor ‘20 out of

10’ points for helping her while another said his consultant was

’brilliant’. A 10 year old boy with learning disabilities recalled an

eye operation he had undergone aged 5 or 6:

Researcher: What happened? Did you go into hospital on your own?

Child: My mum wasn’t allowed to come in with me.

Researcher: Was she not?

Child: Into the theatre

Researcher: Into the theatre. Was she allowed to be with you in the

ward?

Child: Yes. Uh-huh

Researcher: Good

Child: What made me scared most was, there were these tongs, they were

like that…with big bridges with lights on them, you know, and 'oh, oh,

what are they for? What are they for?’

Researcher: Hmm. Hmm.

Child: And there were things all in my mouth.

Researcher: Hmm Hmm

Child: Then everybody was there

Researcher: Ah ha

Child: Then I went ‘Mum!’

Researcher: Hmm. So it’s quite scary. Did it help?

Child: Yeah.

However, none of the children appeared to view impairment as a

'tragedy', despite the close ties between the ‘medical' and 'tragedy'

models of disability (Hevey 1993). They made no reference to feeling

loss or having a sense of being hard done by.

Indeed, for some children it seemed that having an impairment was not

a ‘big deal’ in their lives. When offered a ‘magic wand’ and asked if

they would like to change anything about themselves or their lives,

only three referred to their impairment - two said they would like to

be able to walk and one wanted better vision. One girl with mobility

difficulties compared herself favourably to other children:

When I see people as they two are, I think ‘gosh’ and I'm like glad I

can walk and people see me and I walk like this.

When a boy, aged 9, was asked if he ever wished he didn't have to use

a wheelchair, the reply was:

That's it, I'm in a wheelchair so just get on with it...just get on

with what you're doing.

The children did tell us about what Thomas (1999) calls 'impairment

effects' (restrictions of activity which result from living with

impairment, as opposed to restrictions caused by social or material

barriers). They talked about repeated chest infections, tiring easily,

being in pain, having difficulty completing school work. At the same

time, most seemed to have learned to manage - or at least put up with

- these things. Most children appeared to have a practical, pragmatic

attitude to their impairment. The majority appeared happy with

themselves and were not looking for a 'cure'. However, there were some

indications that a few of the younger children thought they would

outgrow their impairment. The mother of a 9 year old Deaf boy said he

thought he would grow into a hearing adult. (This child had no contact

with Deaf adults). Only one younger child thought she would need

support when she grew up, in contrast to most of the older ones, who

recognised they would need support in some form or other.

Difference

Parents usually thought their children were aware of themselves as

different from other children, but most of the children did not

mention it. Instead, the majority focused on the ways their lives were

similar to or the same as those of their peers. Most said they felt

happy ‘most of the time’, had a sense of achievement through school or

sports and saw themselves as good friends and helpful classmates. They

were active beings with opportunities to mould at least some aspects

of their lives. Most felt they had enough say in their lives -

although some teenagers, like many youngsters of that age, were

struggling with their parents about being allowed more independence.

One girl said of her mother:

She’s got to understand that she can’t rule my life any more...I just

want to make up my own mind now because she’s always deciding for me,

like what’s best for me and sometimes I get angry. She just doesn’t

realize that I’m grown up now but soon I’m going to be 14 and I won’t

be a wee girl any more.

When asked what they would be doing at their parents’ age, the

children revealed very similar aspirations to those of other

youngsters, for example, becoming a builder, soldier, fireman, vet,

nurse or ‘singer and dancer’.

Most problems the children identified were in the here and now: it was

striking that on this subject their responses differed from their

parents’ accounts. Most parents were able to tell us about occasions

where their child had been discriminated against, treated badly or

faced some difficulty - but the children themselves painted a

different picture of the issues which concerned them. Some,

particularly in the older group, reported a high level of boredom;

many of these young people attended special schools and so had few, if

any, friends in their local communities. One teenager explained:

It’s like weird because people at my [segregated] school, they are not

as much my friends as people here ‘cos I don’t know them that much. My

friends past the years, they come to my house but not them. They’ve

never even seen my house.

As Cavet (1998) points out, at this age, leisure and friendship

‘happen’ either in young people's homes or venues like sporting

facilities or shopping centres, neither of which may be accessible to

some disabled adolescents and teenagers.

Fifteen children in the sample had some degree of learning

disabilities. These youngsters made very few references to their

impairment, with only one mentioning her diagnosis. This 13 year old

girl had written a story about herself for the researcher, with whom

she had this exchange as they read it together:

Researcher: What’s that? My name is …

Child: Pat Brownlie, I have De Soto syndrome.

Researcher: Right. Tell me what De Soto syndrome is.

Child: Em…eh…. What is it again?

Researcher: How does it make you feel?...

Child: Different.

It was interesting that, unlike Pat, most of the children focused on

'sameness’: in many cases, it would be hard to avoid or minimise their

difference. Our evidence suggests that it was the way difference was

responded to and managed which was crucial.

Some schools with 'inclusive' policies seemed to take the view that

difference should not even be acknowledged. We were not allowed to

make contact with families through some schools because our research

was about disabled children and they were not to be singled out

(despite the fact that all the interviews were to take place in the

family home). One danger of treating all children 'the same’ is that

rules and procedures designed for the majority do not always fit the

minority. In an example from a mainstream school, one mother told us

that her 14 year old son, a wheelchair user, had been left alone in

the school during fire drill:

He was telling me the other day how they did the fire alarm and

everybody was screaming out in the playground. Richard was still in

the school and everybody was outside. He was saying 'Mum, I was

really, really worried about what happens if there's a real fire.' No

one came to his assistance at all.

Where difference was badly managed, children could feel hurt and

excluded, resulting in the ‘barriers to being’ that Thomas (1999)

identifies. One boy, who attended an integrated unit within a

mainstream school, asked his mother what he had done 'wrong' to be

placed in a 'special' class. Lack of information and explanation had

led him to equate difference with badness or naughtiness.

Some special schools seemed to focus on difference in an unhelpful

way, defining the children in terms of their impairment. At one

school, teachers apparently referred to pupils as 'wheelchairs' and 'walkers'.

A wheelchair user at this school commented: 'It's sad because we're

just the same. We just can't walk, that's all the difference.' Another

pupil at this school told us: 'I'm happy being a cerebral palsy.'

Despite her stated ‘happiness’, it seems unlikely that being publicly

labeled in this way - and then apparently internalising the definition

- would help children develop a rounded sense of self. At the same

time, a couple of children believed that needs relating to their

impairment were better met in special school than they would be in

mainstream, with one boy commenting: A Deaf girl preferred to be :

Where there’s signing, where everyone signs, all the teachers, all the

children.

Researcher: Why is that better than going to a school with hearing

children?

Child: Hearing children – no one signs. I don’t understand them and

they don’t understand me.

Echoing findings made elsewhere (Davis and Watson 2001, Skar and Tam

2001), there were several reports of children in mainstream schools

feeling unhappy with their special needs assistants (SNAs), whose role

is to facilitate inclusion. One older girl was very annoyed that at

break times her SNA regularly took her to the younger children’s

playground when, understandably, she wanted to mix with young people

of her own age. In another case, a SNA always took a pupil into the

nursery class at lunch times, because she (the SNA) was friendly with

the nursery staff!

On the other hand, some schools responded to difference in a positive

way. Many children had

extra aids and equipment at school or were taken out of their classes

for one-to-one

tuition. Much of this support seemed to be well embedded in

daily routines and not made into an issue. The mother of a boy

attending mainstream school recounted:

There was that time, remember, when.... they'd asked a question in the

big hall ... It was 'does anybody in here think they are special?' and

he put his hand up and said 'I am because I have cerebral palsy' and

... he went out to the front and spoke about his disability to

everybody.

It could be argued that encouraging children to see themselves as

‘special’ because they have an impairment is not a positive way

forward. As indicated earlier in this paper in relation to different

types of school, the word ‘special’ can be a euphemism (or

justification) for segregated facilities. ‘Special’ might also be seen

as a somewhat mawkish or sentimental way of portraying disabled

children. However some parents used this word to emphasise that that

their children were unique and valued individuals. Most worked hard to

give the children the message that they were just as good as their

brothers and sisters and any other children, that it was possible to

be different but equal.

Reactions of other people

Nevertheless, children could be made to feel different and of lesser

value by the unhelpful and sometimes hostile words and actions of

others, whether people they knew or complete strangers. These are

another example of what Thomas (1999) refers to as ‘barriers to

being', relating to the psycho-emotional dimension of disability. We

were told of incidents where people unknown to the child had acted

insensitively, for example

• Staring

• Talking down, as if addressing a young child

• Inappropriate comments

• Inappropriate behaviour

• Overt sympathy.

Children who used wheelchairs seemed to be a particular target for the

public at large. An older boy, who had difficulty eating, disliked

going out to restaurants because he was stared at. He used a

wheelchair and got annoyed when people bent down to talk to him as if

he was 'small' or 'stupid':

I don’t mind if it’s wee boys or wee girls that look at me but if it’s

adults…they should know. It’s as if they’ve never seen a wheelchair

before and they have, eh?

A 13 year old girl with learning disabilities described the harassment

which she and her single mother had experienced from neighbours,

including:

The man next door came to our door and rattled the letter box and

shouted ‘come out you cows or I will get you’. So we called the police

and then they did not believe us because I was a special needs.

Other children could also be cruel: almost half the disabled children

had experienced bullying, either at school or in their local

neighbourhood. One boy reported that he was ‘made fun of’ at school

‘about nearly every day.’ His mother reported he had once had a good

day in school because no-one had called him ‘blindie’. Although the

children were very hurt by this kind of behaviour, a few took active

steps to deal with it, reporting the bullying to parents or teachers.

One girl faced up to the bullies herself and was not bothered by them

again. A few were not above giving as good as they got, as this boy’s

response shows:

No, I just bully them back. Or if they started kicking us, I’d kick

them back.

Material barriers

Thomas (1999) describes 'barriers to doing' as restrictions of

activity arising from social or physical factors. These caused

significant difficulties in the children's lives. They included

• Lack of access to leisure facilities and clubs, especially for

teenagers

• Transport difficulties

• Paucity of after-school activities

• Lack of support with communication.

One boy reported he had been unable to go to a mainstream high school

with friends from primary school because parts of the building were

not accessible to him. A 13 year old boy who wanted to go shopping

with his friends at the weekend found that his local Shopmobility

scheme had no children’s wheelchairs. A 14 year old who wanted to

attend an evening youth club at school was told it was not possible to

arrange accessible transport at that time. It was suggested he remain

in school after afternoon lessons ended until the club began.

Understandably, he was not willing to wait around in school by himself

for four hours – nor to attend the youth club wearing his school

uniform.

There was less evidence of material barriers in the accounts given by

children with learning disabilities. Some complained of boredom at

weekends and school holidays, sometimes linked to the fact that they

attended a school outside their neighbourhood and lacked friends

locally. Alternatively they may have been less affected by – or aware

of – the physical barriers affecting some of the children with

physical and sensory impairments.

Discussion

So, children experienced disability in terms of impairment,

difference, other people’s behaviour and material barriers. Some had

negative experiences of the way difference was handled at school; many

encountered hurtful or hostile reactions from other people, and many

also came up against physical barriers which restricted their day to

day lives. Despite all this, most of the children presented themselves

as much the same as others - young people with fairly ordinary lives.

They focused on sameness. Why?

There could be a number of explanations. First, it may be that some of

the children felt they had to minimise or deny their difference. Youth

culture and consumerism exert heavy pressure on young people to follow

the crowd, keep up with others, not to stand out. Disabled youngsters

are by no means immune to such pressure albeit, as Hughes et al (2005)

argue, they may find themselves excluded from ‘going with the flow’.

The concept and practice of ‘passing’ as 'normal' was first identified

by Edgerton (1967) in his longitudinal study of people with learning

disabilities in the US. More recently, Watson et al (2000) reported

that some children with invisible impairments exclude themselves from

the 'disability' category. A significant number of children in our

study were not encouraged to talk about impairment and disability at

home or at school. These attitudes - or pressures - would tend to

discourage children from talking about difference. It is notable that

children at special schools tended to talk more openly about their

impairments - although the schools themselves still seemed to be

operating out of a medical model of disability.

Secondly – and taking a different tack - we could argue that children

in this study are self-directing agents, choosing to manage their day

to day lives and experience of disability in a matter of fact way. It

is important to stress here that the children's (mostly positive)

accounts of their lives differ significantly from earlier research

findings about disabled children based on parents' or professionals'

views which tend to be considerably more negative (see Baldwin and

Carlisle 1994). Some of the older children were also active in

responding to the hostile responses of other people, although there

was less they could do about the structural barriers they came up

against. They were also developing frameworks within which to

understand the behaviors shown to them and, as active agents, chose

not to be categorized by these responses. Impairment, and the

resulting disability, was not seen as a defining feature of their

identities. This concurs with the findings of Priestley et al (1999)

who note that although children could identify the disabling barriers

they encountered, they were still keen to be seen as ‘normal’, if

different, and resisted being defined as disabled. However, there were

exceptions, like the girl who described herself a ‘a cerebral palsy’.

However, we lean towards a third explanation. Perhaps the children

were neither ‘in denial’ nor fully in command of resisting the various

barriers they face. It may be that they did not have a language with

which to discuss difference. We have already noted that they lacked

contact with disabled adults; they did not have positive role models

of disabled people, nor opportunities to share stories about their

lives with other disabled children. Without this framework, it could

be that children strove to be – or appear - the same as their

non-disabled peers. If so, then there is a need for disabled children

to have contact with organisations of disabled people and access to

information and ideas about social models of disability. A

counter-narrative is a critique of dominant public narratives

constructed by people excluded from mainstream society to tell their

own story (Thomas 1999). The social model of disability is a counter

narrative (which has had considerable impact) - but up to now

children’s narratives have played little part in its construction.

Thus, there is a need for the social model to take children’s

experiences on board. How can it do this?

Our findings show that Thomas’ social relational model of disability,

which was developed from women’s accounts of disability, can also

inform our understandings of disabled children’s experiences. First,

despite the fact that the majority had relatively little information

about the cause and in some cases, nature of their impairments,

impairment was a significant part of their daily experience. They

reported various ‘impairment effects’. In addition, our analysis

showed some significant differences in the experiences and perceptions

of those with learning disabilities compared to those with physical

and sensory impairment. Secondly, there was evidence of ‘barriers to

doing’ in the children’s accounts, particularly those with physical or

sensory impairments. They identified various material, structural and

institutional barriers which restricted their activities.

Thirdly, the young people told us about their experiences of being

excluded or made to feel inferior by the comments and behaviour of

others, sometimes thoughtless, sometimes deliberately hurtful. Some

parents strove to give their disabled children positive messages about

their value and worth and fought for them to have an ordinary life,

for example, to attend mainstream schools or be included in local

activities, and some children received good support from teachers or

other professionals. Nevertheless, they could be brought up against

their difference, so to speak, in a negative way by other people’s

reactions, at both a personal and institutional level. In the

children’s accounts, it was these incidents which upset them most,

albeit some showed active resistance to, or rejection of, the labels

or restrictions others sought to impose on them. Thus, in thinking

about disabled childhoods, ‘impairment effects’, ‘barriers to doing’

and ‘barriers to being’ all seem to have a place. Our findings suggest

that the last of these may have particular significance during

childhood years, when young people are going through important stages

of identity formation which may lay the foundations of self confidence

and self worth for years to come.

It is early days and these ideas are no more than a potential starting

point. There is need for a two-way process, in which disabled children

have access to ideas and information about social models of

disability, and social models of disability take account of their

experiences and understandings. To facilitate this process, we need to

open up more space for conversations between disabled

children, disability activists and researchers, and their allies.

References

Ali, Z.., Qulsom F., Bywaters P., Wallace, L. and Singh, G (2001)

Disability, ethnicity and childhood: a critical review of research,

Disability & Society, 16 (7), 949-968

Brannen J. and O' Brien M. (1995) 'Childhood and the sociological

gaze: paradigms and paradoxes' Sociology 29 (4), 729-737

Cavet J. (1998) Leisure and friendship, in: C. Robinson and K. Stalker

(Eds.) Growing up with Disability (London, Jessica Kingsley)

Connors, C. and Stalker, K. (2003a) Barriers to ‘being’; the

psycho-emotional dimension of disability in the lives of disabled

children, paper presented at Disability Studies: Theory, Policy and

Practice, University of Lancaster, 4-6 September.

Connors, C. and Stalker, K (2003b) The views and experiences of

disabled children and their siblings: a positive outlook. (London,

Jessica Kingsley)

Crow, L.. (1996) Including all of our lives: renewing the social model

of disability in: C. Barnes and G. Mercer (Eds) Exploring the divide:

illness and disability. (Leeds, The Disability Press)

Davis, J. and Watson, N (2001) Where are the children’s experiences?

Analysing social and cultural exclusion in ‘special’ and ‘mainstream’

schools, Disability & Society 16 (5), 671-687

Dowling, M. and Dolan, L. (2001) Disabilities - inequalities and the

social model, Disability & Society, 16 (1), 21-36

Edgerton, R. B. (1967) The cloak of competence,: stigma in the lives

of the mentally retarded (San Francisco, University of California

Press)

Finkelstein, V. (1996) Outside, inside out Coalition, April, 30-36

Hevey, D. (1993) The tragedy principle: strategies for change in the

representation of disabled people, in: J. Swain, V. Finkelstein, S.

French and M. Oliver (Eds.) Disabling Barriers - Enabling Environment

(London, Sage)

Hughes, B., Russell, R. and Paterson, K. (2005) Nothing to be had ‘off

the peg’: consumption, identity and the immobilization of young

disabled people, Disability & Society, 20 (1), 3-18

James, A. (1993) Childhood identities: self and social relationships

in the experience of the child. (Edinburgh, Edinburgh University

Press)

James, A. and Prout, A. (Eds.) (1997) Constructing and reconstructing

childhood: contemporary issues in the sociological study of childhood.

(London, Falmer)

Kelly, B. (2005) ‘Chocolate…makes you autism’: Impairment, disability

and childhood identities, Disability & Society 20 (3) 261-276

Mayall, B. (2002) Towards a sociology for childhood (Maidenhead, Open

University Press)

Morris, J. (1991) Pride against prejudice: transforming attitudes to

disability, (London, The Women's Press)

Morris, J. (1993) Gender and disability, in J. Swain, V. Finkelstein,

S. French and M. Oliver (Eds.) Disabling barriers - enabling

environments (London, Sage)

Morris, J. (1998a) Still missing? Disabled children and the Children

Act (London, Who Cares? Trust)

Morris J (1998b) Don’t Leave Us Out: Involving disabled children and

young people with communication impairments, (York, Joseph Rowntree

Foundation)

Morris J (2003) Including all children: finding out about the

experiences of children with communication and/or cognitive

impairments Children and Society, 17 (5)) 337-348

Murray, P. (2002) Hello! Are you listening? Disabled teenagers’

experiences of access to inclusive leisure (York, York Publishing

Services)

Potter C and Whittaker C (2001) Enabling communication in children

with autism, (London, Jessica Kingsley)

Price, J. and Shildrick, M. (1998) Uncertain thoughts on the disabled

body, in M. Shildrick and J. Price (Eds.) Vital signs: feminist

reconstructions of the biological body, (Edinburgh, Edinburgh

University Press)

Priestley, M., Corker, M. and Watson, N. (1999) Unfinished business:

disabled children and disability identity, Disability Studies

Quarterly 19 (2)

Rabiee, P., Sloper, P. and Beresford, B (2005) Doing research with

children and young people who do not use speech to communicate,

Children and Society

Reeve, D. (2002) Negotiating psycho-emotional dimensions of disability

and their influence on identity construction, Disability and Society

17 (5) 493-508

Scott-Hill, M (2004) Impairment, difference and identity, in: J.

Swain, S. French, C Barnes and C Thomas (Eds.) Disabling Barriers -

Enabling Environment (London, Sage)

Shakespeare, T. and Watson, N. (1998) Theoretical perspectives on

research with disabled children, in C. Robinson and K. Stalker (Eds.)

Growing up with Disability, (London, Jessica Kingsley)

Shakespeare, T. and Watson, N. (2002) The social model of disability:

an outdated ideology? Research in Social Science and Disability 2,

9-28

Skar L and Tamm (2001) My assistant and I: Disabled children’s and

adolescents’ roles and relationships to their assistants, Disability &

Society 16 (7) 917-931

Stalker, K. and Connors, C. (2003) Communicating with disabled

children, Adoption & Fostering 27 (1) 26-35

Stalker, K. and Connors, C. (2004) Children’s perceptions of their

disabled siblings: “she’s different but it’s normal for us”, Children

& Society, 18, 218-230

Stalker, K. and Connors, C. (2005) Children with learning disabilities

talking about their everyday lives: in G. Grant, P. Goward, M.

Richardson and P. Ramcharan (Eds.) Learning disability: A life cycle

approach to valuing people, (Maidenhead, Open University Press)

Stone E (2001) Consulting with disabled children and young people, findings

741 (York, Joseph Rowntree Foundation)

Thomas, C. (1999) Female forms: experiencing and understanding

disability (Buckingham, Open University Press)

Thomas, C. (2001) 'Feminism and disability: the theoretical and

political significance of the personal and the experiential' in L.

Barton Disability, politics and the struggle for change (Ed) (London,

David Fulton)

Townsley, R., Abbott, D. and Watson, D. (2004) Making a difference?

Exploring the impact of multi-agency working on disabled children with

complex needs, their families and the professionals who support them

(Bristol, Policy Press)

Waksler, F. (Ed.) (1991) Studying the social world of children:

sociological readings (London, Falmer)

Ward, L (1997) Seen and heard: involving disabled children and young

people in research and development projects (York, Joseph Rowntree

Foundation)

Watson, N., Shakespeare, T., Cunningham-Burley, S., Barnes, C.,

Corker, M., Davis, J. and Priestley, M. (2000) Life as a disabled

child: A qualitative study of young people's experiences and

perspectives: final report to the ESRC, Department of Nursing Studies,

University of Edinburgh

24

POWERPLUSWATERMARKOBJECT6281189 CONCRETE STRUCTURAL I I MATERIAL PROPERTIES PROPERTIES OF

POWERPLUSWATERMARKOBJECT6281189 CONCRETE STRUCTURAL I I MATERIAL PROPERTIES PROPERTIES OF ENFIELD LITTLE HARD HILLS & GARIBALDI DIFFERENTIAL RATE AREA

ENFIELD LITTLE HARD HILLS & GARIBALDI DIFFERENTIAL RATE AREA 8 S YGN AKT I ACA 26411 WYROK

8 S YGN AKT I ACA 26411 WYROK D PTO DE BIENES Y SUMINISTROS ACTA DE AUDIENCIA

D PTO DE BIENES Y SUMINISTROS ACTA DE AUDIENCIA WNIOSEK O OKREŚLENIE WARUNKÓW PRZYŁĄCZENIA DO SIECI ELEKTROENERGETYCZNEJ ANWIL

WNIOSEK O OKREŚLENIE WARUNKÓW PRZYŁĄCZENIA DO SIECI ELEKTROENERGETYCZNEJ ANWIL STANOVENÍ HUSTOTY PEVNÝCH A KAPALNÝCH LÁTEK ÚVOD

STANOVENÍ HUSTOTY PEVNÝCH A KAPALNÝCH LÁTEK ÚVOD  BIOLOGIA I GEOLOGIA 3ESO PROGRAMACIÓ DE AULA ÍNDEX

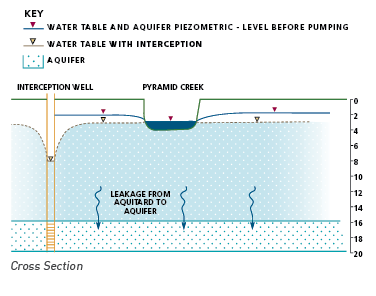

BIOLOGIA I GEOLOGIA 3ESO PROGRAMACIÓ DE AULA ÍNDEX  PYRAMID CREEK SALT INTERCEPTION SCHEME A JOINT WORKS PROJECT

PYRAMID CREEK SALT INTERCEPTION SCHEME A JOINT WORKS PROJECT