remarks at dialogue on ‘the rule of law at the international level’ un headquarters, 15 june 2009 andré nollkaemper university of amst

Remarks at Dialogue on ‘the Rule of Law at the International Level’

UN Headquarters, 15 June 2009

André Nollkaemper

University of Amsterdam

I thank the Rule of Law Unit for inviting me. The topic of the rule of

law at international and national levels has received much attention

by research institutes in my home country, the Netherlands.

Implicitly, it underlies the idea of the Hague as Legal Capitol of the

World. At the University of Amsterdam have just started a major three

year research project on the international rule of law in cooperation

with the Hague Institute for the Internationalisation of the Law. This

panel presents an interesting opportunity to take the debate one step

further.

I was asked to address in particular three points at this Panel.

1.

Links between adherence to the rule of law in international

affairs and domestic affairs and how can each be strengthened by

strengthening the other.

First, I will address the links between adherence to the rule of law

in international affairs and domestic affairs, and how each can be

strengthened by strengthening the other.

This theme is extremely important and, I would suggest, should be at

the heart of the efforts of the United Nations to promote the rule of

law.

Traditionally the rule of law at international level, on the one hand,

and the rule of law at the national level, on the other hand, have

been seen as two separate issues.

To some extent that distinction is still valid.

The rule of law at the international law raises its own distinct

issues, such as the principle of non-intervention and dispute

settlement in the International Court of Justice – that often, though

not always, are quite far removed from rule of law concerns at

domestic level.

Likewise, the rule of law at national level raises its own distinct

issues, for instance problems of corruption at local level, that often

are quite far removed from the rule of law at international level.

We should continue to be aware of these differences and be wary of

attempts to automatic transplanting the domestic rule of law concept

to the international level.

However, it is also clear that there is much overlap. Indeed, the rule

of law at international level and the rule of law at national level

are mutually dependent, and increasingly so. They can strengthen each

other. In the long run rule of law at one level without rule of law at

the other level would not survive.

We can approach this interrelationship and mutual dependency both from

the perspective of international law and from the perspective of

national law.

As to the former: the rule of law at international level cannot do

without a domestic rule of law. In virtually all fields of

international law, compliance with international law is only possible

if there the relevant competent organs at domestic level are governed

by international law. That is obvious for all those areas where

international law substantively deals with the same issues as domestic

law and expressly or implicitly requires implementation at domestic

level, such as international human rights, international criminal law

and international environmental law. In these areas domestic law must

reflect international law.

The point is more generally true, however. The basic rules of

international law, that stipulate that a state shall not go to war

against another state and, if it does, shall not kill innocent

civilians, that are mostly thought of as interstate affairs, are

powerless if there is no connection between that international norm

and domestic law.

Also the principle of R2P inevitably rests on implementation of human

rights and principles of international criminal law at the domestic

level.

The full effect of international rights and obligations requires and

presupposes a domestic rule of law. Indeed, one cannot really conceive

of a rule of law at the international level, without a domestic rule

of law.

The mutual dependency between international law and domestic law also

is clear from the perspective of the rule of law at domestic level.

International law, particularly international human rights law,

strengthens and supports the domestic rule of law. It can protect the

autonomy of domestic courts vis-à-vis the political branches, and

protect individual rights against earlier of subsequent domestic law

that might violate such rights. Indeed, it is the permanent protection

provided by international law that makes clear that the rule of law is

more than the rule by law, which could be changed at the whims of

changed domestic political preferences.

It is telling that for instance in Eastern-Europe, after 1989, many

states opted for an automatic incorporation of international human

rights law, which helped to stabilize the political system and make it

less vulnerable to radical political changes.

From this close relationship, a number of policy recommendations would

seem to follow that are relevant to the work of the UN on the rule of

law.

First, policies to strengthen rule of law should necessarily aim to

improve domestic procedures and policies for the implementation of

international obligations. This has been said often before. However,

it remains a critical task in many states, where the translation to

domestic level is deficient, undermining the degree to which

international law can actually rule.

Second, while the task of domestic implementation is not at all

confined to human rights and has a much wider ambit, it also is clear

that human rights are particularly relevant for the rule of law and

that special attention should be given to proper domestic

implementation to international human rights standards. The almost

universal support for the relevant treaties make this the proper

benchmark of all rule of law policies.

This aim goes beyond the aim to make international human rights law

effective –, it has the power to entrench domestically the rule of law

and replacing the rule by law by the rule of law.

Third, we should not focus only at implementation of international

standards, but also to the structural institutional arrangements, in

particular the power of the courts to give effect to international

law, notably human rights standards. As noted in several of the SG

reports, these issues need to be addressed comprehensively. Rule of

law is more than just having a set of laws, whether or not in

conformity with international law. It is also about setting up

institutions that are sensitive to international and that provide

conditions for application and continuity of such laws.

The importance of this point goes beyond making international law

effective. It should also ensure that state organs in their external

relations are subjected to rule of law standards. Here lies a crucial

connection between the rule of law at international and the rule of

law at national level. Precisely the lack of power of courts to review

foreign policy issues domestically underlies much of the rule of law

concerns internationally.

Fourth, rule of law promotion, in particular in the area of

constitutional reform, should abandon the idea that international law

is neutral as regards the way international law domestically gives

effect to international law. There is no doubt that constitutional

models that allow for direct effect of human rights and that give

human rights a hierarchically higher position than ordinary laws

provide better guarantees for a sustainable rule of law, both

nationally and internationally – a fact clearly recognized by the

Human Rights Committee and the Committee on Social, Economic and

Cultural Rights. Not in all countries can such models be adopted, but

there are many intermediate positions, that may go some way to protect

the international and national rule of law.

The task that follows from these four points is much more complicated

than it may seem. Each of these four points, seeking to improve the

connection between the international and the domestic level, are

subject to two major qualifications.

First, it is clear that constitutional, legislative and institutional

reform aimed at implementing international law leads to nothing unless

embedded in a much wider sets of policies aimed at rule of law reform.

There is a long list of failed projects in rule of law development,

from judicial reform to human rights institutions to democracy

building – and we should be aware of the lessons learned in all such

failed project. These lessons are above all that we should recognize

the diversity of local context and not seek a one size fits all

approach, even where it concerns international law.

The second qualification is that all of this is only going to work if

protection of the rule of law does not only focus on domestic levels;

but extend to international institutions, and more generally the

processes of international law-making and law-adjudication. These

should be embedded in a proper rule of law governed context – not

identical but in certain respects comparable to the rule of law

standards as we seek domestically. This holds for the Security Council

sanctions, but there are many other examples.

Recent evidence suggests very clearly that states willingness to allow

international law domestically, in turn creating the conditions for

external international observance, is contingent on the substantive

rule of law quality at international level.

Constitutional reform supported by the UN appropriately should take

into account these sensitivities, indeed warning against a full and

unqualified monistic approach. It is telling that even the

Netherlands, often heralded as a monist state that grants event

supremacy to international law over the constitution, has initiated

discussions on the need to protect constitutional values against the

effect of international decisions that would fall short of rule of law

standards

Recognizing that fundamental human rights are shared between

international and domestic law is key here. It is precisely because of

the domestication of these rights, and the protection they may provide

against arbitrary and oppressive laws, that continental European

states have been able to accept full power of international law – not

blindly, but conditional on its compatibility with such fundamental

rights.

In conclusion, there thus is a need for a comprehensive rule of law

policy, including both the international and the national level,

recognizing the diversity between states. I do note that the work of

the UN has come a long way. Whereas in the Millennium Declaration

international and domestic rule of law concerns were largely

separated, the 2008 SG report in various ways does recognize the links

between such concerns and as such provides a proper platform for

further pursuing this agenda

2.

What steps can be taken to enhance action by Member States and the

Organization to combat impunity and strengthen universal justice

The second item that I was asked to address is what steps can be taken

to enhance action by Member States and the Organization to combat

impunity and strengthen universal justice.

First of all it should be noted that the approach to the international

rule of law thus far has been somewhat imbalanced, focusing strongly

and almost exclusively on individual criminal responsibility and

criminal justice and excluding responsibility of states and

international organizations. International responsibility of all

subjects of international law is key to any concept of the

international rule of law.

If I nonetheless confine myself to criminal justice, it seems that the

key elements of the way forward here are clear: strengthening

adherence to the ICC, and supporting its work through effective

cooperation.

However, it is clear that this will cover only a very narrow part of

what is necessary to combat impunity. Here too, an inextricable link

exists between the international and the national level. A combination

of jurisdictional limits, limits to trial possibilities, enforcement

limitations and protection of sovereign entitlements of states imply

that the vast majority of trials of individuals suspected of

perpetrating criminal offences in the context of mass atrocity

situations is expected to take place before the domestic courts of the

state in whose territory the events took place, or in the state of

nationality of the perpetrators.

In the 2004 report on transitional justice it still was written that

depite the possibilities at national level, effort should be made to

strengthen justice at the national level. I would think that if this

report were written now, the emphasis would be laid in the ohter

direction.

Domestic trials do not only present a way to reduce costs and improve

enforcement capabilities, they may also enjoy greater social

legitimacy than trials conducted by international courts that are far

removed from the events discussed on trial and are sometimes accused

of being ignorant of local conditions and history, offering the

accused an inhospitable forum, and embracing a selective approach

toward some parties to some conflicts.

In addition to strengthening the ICC, then, combating impunity will

require a strengthening of domestic capacity. This is to some extent a

question of domesticating appropriately international crimes. It is

more a matter of institutional power, independence and ability to

conduct trials in post conflict setting. Of the many points that

require action, let me just mention two.

First, there is a need to optimize the the impact of international

court procedures on domestic procedures for putting to trial the

perpetrators of mass atrocities. This may include the formation of

formal – or semi-formal links between national and international

courts, closer alignment of procedures and work methods, the

generation of incentives for national courts to prosecution,

reallocation of budgets, sharing of staff, lending of support by

international to the operation of national courts, etc. Such policies

would reflected that at least to some extent, international and

domestic criminal courts are involved in a common endeavour to secure

justice, and do not operate in isolation. At present we are conducting

a major project for the EU on this topic, and the outcomes may well of

interest to the work of the UN on rule of law promotion.

Second, we also need to recognize that international criminal courts

may not be best positioned to strengthen the capacity of national

courts. After all, they are organized with a view to conduct trials,

not to engage in capacity buildigng or judicial training. It thus is

important that better links are established between the activities of

international courts, on the one hand, and the variety of rule of law

supporting procedures, througth the UN or otherwise, on the other.

Improving domestic criminal justice thus will require a partnership

between UN, international criminal tribunals that may operate outside

the framework of the UN , and a variety of other institutions.

3.

How can the role of the United Nations, including the

International Court of Justice, in the peaceful settlement of

disputes be strengthened and what steps can be taken to promote

other international dispute resolution mechanisms

The third item that I was asked to address was ‘How can the role of

the United Nations, including the International Court of Justice, in

the peaceful settlement of disputes be strengthened and what steps can

be taken to promote other international dispute resolution mechanisms’

In contrast to the first two items, this is a topic that relates

primarily to the rule of law at international levels.

However, primarily does not mean exclusively. A major contribution to

prevention of international disputes can be offered by domestic courts

that are able and capable to handle international claims. There are

encouraging signs across the globe that show that domestic courts

increasingly see their role in this way. These practices, aiming at

prevention of international disputes, should be strengthened.

A further obvious link, recalled in the GA resolution adopting the

Millennium Declaration, is that the rule of law requires that

decisions of international courts can only actually contribute to

settlement of disputes if they are properly effectuated at domestic

level. This too is an aspect where rule of law at domestic level and

at international level meet.

Turning to international dispute settlement itself, the first thing to

note that we have enormous steps forward in the past decades. More use

is made than ever before of international dispute settlement

proceedings. Indeed, it is as a result of this progress that it has

become fashionable again to speak of an international rule of law in

the first place.

That being said, there is much work to be done. Let me address briefly

two aspects.

First, states have made clear that they have a preference for treaty

based institutional arrangements over bilateral dispute settlement

outside such frameworks. The various monitoring and non-compliance

procedures under multilateral environmental arrangements are a case in

point. I should recall that in the SG definition of rule of law,

accountability is a key element of the rule of law, distinct from

adjudication by international courts. Even if these institutionalized

procedures do not lead to formal adjudication, they may perfectly well

provide adequate accountability and as such contribute to the rule of

law. This is one of the areas where the international rule of law

should take into account the specific nature of the international

legal system.

With the progressive institutionalization of international law,

efforts to strengthen the international rule of law should not be

confined to strengthening classic dispute settlement, but should also

focus as the lessons that have been learned so far from

institutionalized procedures for monitoring compliance, and to

identify to what extent they can be extended to other

treaty-arrangements.

Second and finally, a few words on the ICJ and the UN. The number of

cases before the ICJ is larger than ever before. But this does not

necessarily mean that the role of the Court in the system of dispute

settlement is increasing. Probably the reverse is true. As states more

and more look elsewhere for settlement of their disputes, the relative

role of the ICJ decreases.

One could argue that this does not necessarily present a problem and

that it does not matter where and how disputes are adjudicated, as

long as they are adjudicated. That may be so, but there is one caveat

to be made.

If the rule of law at international level exists, it should have a

common substantive core, in the sense that it is based on a relatively

clear set of fundamental principles that is shared across the

international legal order. From that perspective, we are witnessing

serious countervailing trends due to the specialization of

international law and the formation of functional treaty based regimes

with their own dispute settlement proceedings.

International courts in these treaty based regimes, such as the ECHR

have indicated that they are willing to listen to the center, but then

that center should be there. That center is the ICJ and more generally

the UN. The challenge is to preserve and perhaps strengthen the

position of the ICJ in relation to the large number of special

regimes.

This may in part be done through inclusion of clauses for compulsory

jurisdiction in particular treaty arrangements, which hold more

promise than declarations under article 36(2); development of the

concept of article 48 of the Articles on State responsibility,

allowing non-injured states to bring a claim to the Court, and

strengthening its power to provide advisory functions.. But perhaps

more important for the authority of the Court than increasing the

number of its cases, is how the Court itself defines its role. In the

drafting of its judgments the Court itself holds a key to enhancing

the authority of the court vis-à-vis other international courts and to

hold the center in a rule of law based in international system.

7

ETIČKI KODEKS DRŽAVNIH SLUŽBENIKA I OPĆE ODREDBE PREDMET ETIČKOG

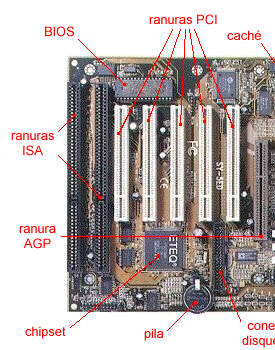

ETIČKI KODEKS DRŽAVNIH SLUŽBENIKA I OPĆE ODREDBE PREDMET ETIČKOG TEMA WINDOWS CONTENIDO 01 COMPONENTES DEL ORDENADOR EXPOSICIÓN ¿QUÉ

TEMA WINDOWS CONTENIDO 01 COMPONENTES DEL ORDENADOR EXPOSICIÓN ¿QUÉ STAVBA SO 01 POLYFUNČNÝ DOM STUPEŇ PD PROJEKT PRE

STAVBA SO 01 POLYFUNČNÝ DOM STUPEŇ PD PROJEKT PRE SURAT PERNYATAAN BERSEDIA DIANGKAT MELALUI INPASSINGPENGANGKATAN PERTAMAPERPINDAHAN JABATAN) KE

SURAT PERNYATAAN BERSEDIA DIANGKAT MELALUI INPASSINGPENGANGKATAN PERTAMAPERPINDAHAN JABATAN) KE UNIDAD DIDÁCTICA EL MÉTODO CIENTÍFICO Y LA MEDIDA

UNIDAD DIDÁCTICA EL MÉTODO CIENTÍFICO Y LA MEDIDA RADICACIÓN 25000233700020130108901(23112) DEMANDANTE HIGH MEDICINE SA FALLO PACTOS O

RADICACIÓN 25000233700020130108901(23112) DEMANDANTE HIGH MEDICINE SA FALLO PACTOS O GRUPO 38 FECHA DE INGRESO DD MM AA INGRESO

GRUPO 38 FECHA DE INGRESO DD MM AA INGRESO A DULLAM HOMES HOUSING ASSOCIATION LIMITED UNLOCKING POTENTIAL SKILLS

A DULLAM HOMES HOUSING ASSOCIATION LIMITED UNLOCKING POTENTIAL SKILLS METODOLOGÍA PARA LA TOMA DE DECISIONES EN LA VIDA

METODOLOGÍA PARA LA TOMA DE DECISIONES EN LA VIDA